Censorship Issues in Korean Cinema, 1995-2002

by Darcy Paquet

Lies, dir. Jang Sun-woo.

The following paragraphs are intended to provide an overview of the censorship situation in Korea since 1995. I am using the word censorship in its broadest sense, meaning the various institutions or practices that bring about modifications to the finished product which filmmakers intend to present to their audience. Prior to the mid-1990s there was a tremendous degree of direct governmental interference in the film industry, but since 1995 most censorship issues have been linked with the practice of classifying films.

What organization is responsible for classifying films and videos in South Korea?

South Korea has a Media Ratings Board which is in charge of assigning classifications to films, videos, computer games, and other media released for public viewing (a separate board exists for television). In 1995, government censorship of films was ruled unconstitutional and so the former governmental censorship board was disbanded. The less powerful Media Ratings Board -- made up of film professors, directors, lawyers, and other individuals with or without connection to the film industry -- has taken its place. The board has a bilingual website at http://www.kmrb.or.kr.

The Media Ratings Board has undergone some restructuring and changes in personnel since its inception, most recently in mid-2002. However the board chairman, veteran director Kim Soo-yong (who had his own highly publicized struggles with government censorship in the 1980s), has remained in charge of the board since the late 1990s. New board members have been chosen by Kim himself in consultation with the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, a process that some have criticized as being inappropriate.

Over its history, the board also appears to have experienced some internal dissent, as evidenced by the resignation of respected director Park Chong-won in late 1999 over the controversy surrounding Lies, and the resignation of several members over the controversy surrounding Too Young To Die in 2002.

What are the classifications for films/video?

Currently the following categories exist: General, 12+, 15+, and 18+. An 18+, for example, indicates that only those aged 18 years or older may enter the theater. There are no exceptions for attending with a parent or legal guardian, such as in the U.S. The 15+ rating was eliminated in late 1999 but reinstated in April 2000.

News reports indicate that there has been pressure in the past to change the 18+ rating to a 19+ rating to coincide with the legal age for adulthood. At the moment this appears highly unlikely to happen, however. In addition, the government has proposed an additional, "Restricted" classification for films which may only be screened at specially-designated adult theaters. However this measure will have to be passed by South Korea's National Assembly, where it faces opposition.

A study of ratings over the years 2000 to 2002 has also indicated that the 15+ rating is becoming more common, as films which may have received an 18+ rating in the past are being given the lower rating.

Note that the above classifications are based on the Korean (originally Chinese-derived) system for counting age, which differs slightly from that used in the West. Infants are considered to be one year old at birth, and people become a year older on the first day of the year, rather than on one's birthday. For shorthand one may subtract a year from the above ages to roughly coincide with Western ages.

What elements are most likely to cause problems with classification/censorship, and have there been any controversies regarding this in the past?

In recent years, sexual content has been the key issue that pits filmmakers against the Media Ratings Board. Pubic hair and male or female genitalia are disallowed on the screen, unless they are digitally blurred. In rare cases, extreme violence, obscene language, or certain portrayals of drug use may also become an issue.

Although the Media Ratings Board does not technically have the power to cut or ban films on its own, it frequently uses its influence to pressure film companies to cut or modify scenes which it feels to be inappropriate. It often holds informal consultations with film companies to negotiate the cuts needed to achieve a desired rating.

Although the Media Ratings Board does not technically have the power to cut or ban films on its own, it frequently uses its influence to pressure film companies to cut or modify scenes which it feels to be inappropriate. It often holds informal consultations with film companies to negotiate the cuts needed to achieve a desired rating.

In the past, the board has on several occasions deemed a film unfit to be released, and so it refused to assign a rating. After receiving this rejection, producers were obligated to wait two months before reapplying (presumably with the offensive material removed voluntarily). The board was strongly criticized for utilizing this power to effectively ban films, which critics claimed was unconstitutional. The first widely-publicized example of this was the Korean film Yellow Hair (pictured), which was rejected once in early 1999 before being granted an 18+ rating on its second application, after a sex scene between two women and one man was partially cut and digitally altered.

The most famous example of this phenomenon was the Korean film Lies, which was rejected days before receiving an invitation to compete at the 1999 Venice Film Festival, and then rejected again two months later. On its third application the film received an 18+ rating after several scenes were cut and some lewd language between two high school girls was removed from the audio track. The film opened in early 2000 and was subsequently pulled early from theaters (seemingly due to public pressure) after four weeks on the screen.

In October 2000, the film Happy Day became the first animated feature to be refused a rating by the board.

Notable examples of foreign films which have been refused a rating include Wong Kar-wai's Happy Together, which was rejected in 1997 but subsequently released in a cut version. Eyes Wide Shut was also delayed for close to a year due to negotiations with the ratings board.

Some critics have also noted that the board has assigned 18+ ratings to films which received a comparatively lower classification in their home countries. Several Japanese films in particular, including Tomie:Replay and Ring 3: Spiral have been delayed or pulled from release after failing to receive an expected 15+ rating.

In September 2001, a court case brought against the board by distributor Indiestory regarding the film Yellow Flower (not to be confused with Yellow Hair) reached Korea's Constitutional Court. The court ruled that the board had been acting illegally by refusing the film a rating, stating that it was in essence governmental censorship. Henceforth the board has been prohibited from rejecting feature films outright, although the practice continues for video releases (the domain of Korea's soft porn industry).

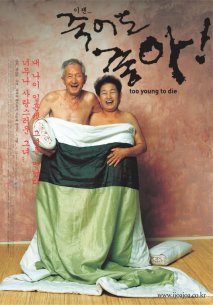

On July 23, 2002, another controversy erupted when the board voted 5-4 to issue a Restricted rating to the film Too Young To Die (pictured), a fictional account of a real-life couple in their 70s who meet and rediscover sex (the film had previously screened at the Cannes International Film Festival's Critics' Week). Given that legislation concerning the Restricted rating had still not been enacted, the film was effectively banned from a theatrical release. A considerable amount of press coverage followed, with filmmakers putting together petitions and small protests to voice their opposition to the board. The film also received votes of support from the national teacher's union and the Korean Federation of Trade Unions.

May Film, the production company of Too Young To Die, eventually received an 18+ rating for the film in late October after they darkened some problematic sex scenes (no cuts were made).

This was actually the second instance of a film receiving a restricted rating, the first being the 290-minute North Korean documentary Animal Copulation, which was given the Restricted rating on May 21, 2002 for its portrayals of animal genitalia. The documentary had previously screened on public television in North Korea.

Has censorship become more relaxed in South Korea?

From a historic point of view, Korea has made great strides in reducing the level of government censorship in filmmaking. This has largely been a reflection of the political changes that have transformed South Korea over the past decade from a military dictatorship into a lively democracy. A generational change in the film industry and the persistent efforts of directors like Jang Sun-woo have also helped to widen the range of the permissible in Korean cinema.

It should be noted that (as in many countries) Korean filmmakers are still under great economic pressure from their own distributors and production companies to keep films under two hours in length, and this results in many scenes being cut from contemporary releases. In today's industry, these economic considerations are a much greater constraint on filmmakers than governmental censorship.

Lastly, in rare cases films may even face pressure from international film festivals, such as in 2000 when the Cannes International Film Festival insisted on cuts being made to Im Kwon-taek's Chunhyang before inviting it to its Competition Section. Chunhyang is therefore an example of a Korean film whose international release contains cuts, while the domestic print remains uncut.