2001

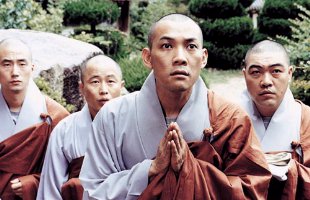

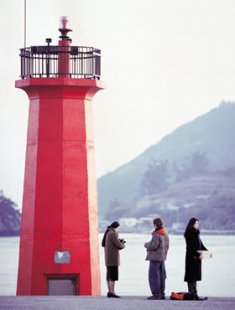

From left: "Friend", "Musa", "One Fine Spring Day", "Bungee Jumping of Their Own"

The past few years have been very strong for Korean cinema, but 2001 marks a new plateau in terms of box-office clout. Led by such smash hits as Friend (the best-selling Korean movie of all time), My Sassy Girl, My Wife is a Gangster, Kick the Moon, Hi Dharma, Guns & Talks, and Musa -- all of which drew more than two million viewers -- Korean cinema has approached a 50% market share in 2001. With Hollywood films accounting for less than 40% of the market, Korea has become just about the only place in the world where local films outdraw Hollywood.

Nonetheless, the presence of so many blockbuster films has not meant the death of more artistic work. Visitors to the 2001 Pusan Film Festival who had heard that Korean cinema had "gone commercial" were pleasantly surprised by the high number of original, quality films on display. Films such as One Fine Spring Day, Flower Island and Take Care of My Cat have been eagerly sought after by foreign festivals, and Korean cinema's rapidly expanding talent base gives hope that the industry will continue to make good films long into the future.

Reviewed below: I Wish I Had a Wife (Jan 13) -- A Day (Jan 20) -- Tears (Jan 20) -- Bungee Jumping of Their Own (Feb 3) -- Last Present (Mar 24) -- Friend (Mar 31) -- Failan (Apr 28) -- Kick the Moon (Jun 23) -- My Sassy Girl (Jul 27) -- Sorum (Aug 4) -- Musa (Sep 7) -- One Fine Spring Day (Sep 28) -- My Wife is a Gangster (Sep 28) -- Nabi (The Butterfly) (Oct 13) -- Guns & Talks (Oct 12) -- Take Care of My Cat (Oct 13) -- Waikiki Brothers (Oct 27) -- Hi, Dharma (Nov 7) -- Wanee & Junah (Nov 23) -- Flower Island (Nov 24) -- Volcano High (Dec 8).

| Korean Films | Nationwide | Seoul | Release Date | Weeks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Friend | 8,134,500 | 2,579,950 | Mar 31 | 15 |

| 2 | My Sassy Girl | 4,852,845 | 1,765,100 | Jul 27 | 10 |

| 3 | Kick the Moon | 4,353,800 | 1,605,200 | Jun 23 | 10 |

| 4 | My Wife is a Gangster | 5,180,900 | 1,466,400 | Sep 28 | 8 |

| 5 | Hi, Dharma | 3,746,000 | 1,304,200 | Nov 7 | 8 |

| 6 | My Boss, My Hero | 3,302,000 | 1,229,100 | Dec 8* | 9 |

| 7 | Guns & Talks | 2,227,000 | 896,500 | Oct 12 | 7 |

| 8 | Musa | 2,067,100 | 873,600 | Sep 7 | 6 |

| 9 | Volcano High | 1,687,800 | 593,200 | Dec 8* | 5 |

| 10 | Bungee Jumping Of Their Own | 947,000 | 507,400 | Feb 3 | 11 |

| All Films | Nationwide | Seoul | Release Date | Weeks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Friend (Korea) | 8,134,500 | 2,579,950 | Mar 31 | 15 |

| 2 | My Sassy Girl (Korea) | 4,852,845 | 1,765,100 | Jul 27 | 10 |

| 3 | Harry Potter... (U.S.) | 4,030,000 | 1,672,000 | Dec 14* | 8 |

| 4 | Kick the Moon (Korea) | 4,353,800 | 1,605,200 | Jun 23 | 10 |

| 5 | My Wife is a Gangster (Korea) | 5,180,900 | 1,466,400 | Sep 28 | 8 |

| 6 | Hi, Dharma (Korea) | 3,746,000 | 1,304,200 | Nov 7 | 8 |

| 7 | My Boss, My Hero (Korea) | 3,302,000 | 1,229,100 | Dec 8* | 9 |

| 8 | Shrek (U.S.) | 2,344,700 | 1,123,200 | Jul 06 | 6 |

| 9 | Pearl Harbor (U.S.) | 2,261,100 | 1,081,627 | Jun 2 | 7 |

| 10 | The Mummy Returns (U.S.) | 2,341,800 | 954,700 | Jun 16 | 7 |

* Includes tickets sold in 2002.

Market share: Korean 50.1%, Imports 49.9% (nationwide)

Films released: Korean 65, Imported 306

Total attendance: 89m admissions

Number of screens: 818 (nationwide)

Exchange rate (2001): 1276 won/US dollar

Average ticket price: 5,860 won (=US$4.59)

Exports to other countries: US$11,249,573

Average budget: 1.62bn won + 0.93bn p&a costs

Source: Korean Film Council (KOFIC).

Short Reviews

These are some reviews of the features released in 2001 that have generated the most discussion and interest among film critics and/or the general public. They are listed in the order of their release.

Long before this film hit the theaters, I Wish I Had a Wife drew interest for its pairing of two of Korea's most respected stars: Sol Kyung-gu (Peppermint Candy) and Jeon Do-yeon (Happy End). In their first crack at romantic comedy, Sol and Jeon take on parts which, although lacking the emotional extremes of their previous roles, form the very heart of this charming film.

Sol plays a lovesick bank teller who can't get marriage off his mind. He records videos for his future wife, telling her how curious he is to find out who she will turn out to be. When he meets a former classmate (played by Jin Hee-kyung), he thinks he's finally found his match. Jeon, meanwhile, plays a teacher who works across the street from his bank. After a few accidental meetings, she works up the courage to ask him out, but is rudely rebuffed.

Sol plays a lovesick bank teller who can't get marriage off his mind. He records videos for his future wife, telling her how curious he is to find out who she will turn out to be. When he meets a former classmate (played by Jin Hee-kyung), he thinks he's finally found his match. Jeon, meanwhile, plays a teacher who works across the street from his bank. After a few accidental meetings, she works up the courage to ask him out, but is rudely rebuffed.

This is the debut work of director Park Heung-shik, who worked as assistant director to Hur Jin-ho for Christmas in August (1998). The influence of the latter film can be seen in I Wish I Had a Wife: in its visual style, its grounding in everyday life, and also in a subtle reworking of Christmas's famous umbrella scene.

At times the film's music recalls a Sleepless in Seattle or When Harry Met Sally, but I Wish I Had a Wife is a much different kind of movie. Content to revel in the ordinary, it lingers on unimportant details and its heroes' various quirks. Although at times this comes at the expense of plot, it imparts to the film a sense of honesty, as well as an unhurried pleasure. By the latter half of the film we begin to feel quite intimate with the characters.

Ultimately this movie feels like a comfortable old pair of jeans. While it makes little effort to leap out and grab one's attention, viewers will be pulled in by its light humor and the way it makes its characters' lives feel so familiar. (Darcy Paquet)

I was scared, really scared, when I turned to the back cover of the DVD for Han Ji-sung's A Day and saw the couple sitting by a tree. At the sight of that image, I immediately flashbacked to the top-grossing Korean film of 1997, Lee Jeong-guk's The Letter, since a tree had significance in that film. The Letter, to me, exemplifies a melodrama gone wrong, horribly cheezy and forced. Still, it was successful at the Korean box office, so perhaps those in charge of marketing A Day felt an allusion to the imagery of The Letter would allow A Day to dovetail that film's success even though such a scene by a tree never occurs in A Day.

A Day tells a story of more than one day in the life of the marriage between Kang Jin-won (Ko So-young) and Lee Suk-yun (Lee Sung-jae). They are a couple who very much wants a child but have had trouble conceiving. When they are finally successful, with the help of modern medical technology, their fantasies about the family life they feel should emerge are challenged by further obstacles that arise. The film becomes a story on how this couple processes their adversity and how it strengthens rather than weakens their bond.

A Day tells a story of more than one day in the life of the marriage between Kang Jin-won (Ko So-young) and Lee Suk-yun (Lee Sung-jae). They are a couple who very much wants a child but have had trouble conceiving. When they are finally successful, with the help of modern medical technology, their fantasies about the family life they feel should emerge are challenged by further obstacles that arise. The film becomes a story on how this couple processes their adversity and how it strengthens rather than weakens their bond.

Thankfully, A Day does not end up being to the letter of The Letter. It comes close at moments, particularly due to the lesser performance of Lee Sung-jae who initially fails in making the playful moments that lovers share convincible. Such is disappointing because Lee's previous work in Bong Joon Ho's Barking Dogs Never Bite was exemplary. Still, Lee's character does grow on you, with the help of a confident performance by Ko So-young as his wife, and you begin to appreciate him more. Most of the fights and intimate moments between the couple are believable and notable in what they convey about the growth of the characters and the moral dilemmas their predicament poses.

The standout performance, however, is by Kwon Hae-hyo, the only tolerable presence in an excruciating film of the same year, O Ki-hwan's Last Present. Kwon is masterful in his comic delivery in a small part as the manager of a store that sells baby items. (As evidence of his skill, let me note that a smirk just emerged on my face while thinking about his brief appearance.) I look forward to a vehicle that allows Kwon to shine in a feature role developed from his gifted repetoire. Kim Chang-won also delivers a finely sober performance as the couple's doctor and indirect marriage counselor.

Without moralizing a message upon the audience, A Day presents a moral quandry that, thankfully, leaves the decision up to the parties most directly effected. While watching the film, I found myself referencing one of my favorite novels by my favorite Japanese writer, both of which will go unmentioned because such would risk revealing main aspects of the plot. Although very different works, particularly in their intended audience, A Day a popular drama and the book a major literary work, there is a similarity in the point of struggle. Whereas that book's little bird tells a tale of a man choosing an isolated struggle with his responsibility to act on life's random trials, A Day addresses the communal struggle of this couple while hinting at the professional quandries and societal constraints around them. Considering how important that book is to me, perhaps that is why I was so touched by this film while having no reference points of comparison in my life of involuntary singlehood.

Although not every director of melodramas has the patience of Hur, the economy of Kaurismaki, or both like Ozu, Han, for the most part, directs a compelling story of love surviving the trials and tribulations that life brings to us, reminding us the fantasy is always far from the reality. And the strong performance by Ko (which won the Grand Bell Award for Best Actress) and wonderful supporting roles by Kwon and Kim keep this film from entering the histrionics and kitsch that all melodramas risk. Although arguments could be made for more deserving directors of best of the year honors, Han's work in A Day definitely warranted the consideration and his winning of the Grand Bell for Best Director is one I can personally live with. (Adam Hartzell)

Garibong-dong is a district in Seoul which has become known for its population of homeless teens. Set within this locale, Tears details the lives of four young runaways who, despite their differences, join together in an uneasy partnership.

Although Tears is director Im Sang-soo's second film, he was envisioning it in his mind years before the release of his debut feature Girls' Night Out (1998). In the mid-nineties, he developed an interest in the lives of homeless teens and decided to live among them for five months, trying to understand them and earn their trust. Tears is based on this experience, and although certain dramatic elements of the plot are fictional, Im insists that most all of the situations and conversations are taken from real life.

Although Tears is director Im Sang-soo's second film, he was envisioning it in his mind years before the release of his debut feature Girls' Night Out (1998). In the mid-nineties, he developed an interest in the lives of homeless teens and decided to live among them for five months, trying to understand them and earn their trust. Tears is based on this experience, and although certain dramatic elements of the plot are fictional, Im insists that most all of the situations and conversations are taken from real life.

Shot on digital video, Tears captures the gritty feel of its protagonists' lives. Ultimately, however, the film is less concerned with exposing the excesses of street life than in coaxing us to side with the teens, or at least see life from their point of view. Im tries hard to make his heroes seem human and to show us the insecurity behind their tough behavior. Shots of abusive parents or cruel employers remind us of the forces that have shaped these kids' lives.

Yet the film's most memorable scenes are probably its quietest, when the kids carouse on a muddy beach or creep towards sexual intimacy. These moments hold enough gloom and beauty to let us picture these kids either in or out of their present lives.

Particularly worthy of praise are the group of debut actors who star in this film. Without their guts and talent, Tears would never work. Although similarly-themed works have been shot before in Korea and elsewhere, Tears remains worth seeing for its finely-drawn characters and personal approach. (Darcy Paquet)

Despite being shackled with perhaps the dumbest English title in history of Korean film, Bungee Jumping of Their Own has drawn interest both in Korea and abroad for its unusual story and the fine performances of its actors. Its strength at the domestic box-office came as somewhat of a surprise, particularly given that it flirts with the issue of homosexual relationships and the hostile reception they usually receive in Korea.

The film opens in 1983, when university student In-woo becomes infatuated with a woman who shares his umbrella in a rainstorm. Their developing relationship is presented in fragments that highlight the awkwardness and humor of their situation, and yet the underlying seriousness of their feelings end up forming the crux of the story. After learning that In-woo must leave for his obligatory two-year service in the military, we jump 17 years into the future to find him as a high school teacher, married to another woman. His earlier insecurities appear to have vanished, and he commands the respect of his students for his passion and his willingness to stand up for their rights...

The film opens in 1983, when university student In-woo becomes infatuated with a woman who shares his umbrella in a rainstorm. Their developing relationship is presented in fragments that highlight the awkwardness and humor of their situation, and yet the underlying seriousness of their feelings end up forming the crux of the story. After learning that In-woo must leave for his obligatory two-year service in the military, we jump 17 years into the future to find him as a high school teacher, married to another woman. His earlier insecurities appear to have vanished, and he commands the respect of his students for his passion and his willingness to stand up for their rights...

This is the debut film by director Kim Dae-seung, who worked for many years with Im Kwon-taek as an assistant director for such films as Sopyonje, The Taebaek Mountains, Festival, Downfallen, and Chunhyang. Although Bungee Jumping of Their Own does not feel in any way like an Im Kwon-taek film, the time Kim spent as an assistant director appears to have paid off, and he is surely a director to keep an eye on. Each of the film's three major segments contain vivid scenes, presented in a manner that strips them of their sentimentality. The film's opening is striking in its visuals, humor and sadness, while the scenes shot in the present contain an unusual energy. Later in the film the mood turns much more serious and issue-oriented, in an unusual plot twist that I omitted on purpose from the above synopsis.

One effect of these various moods is that it showcases the acting of Lee Byung-heon, who since his role in Joint Security Area has earned great respect for his talent (as opposed to his looks, which have always attracted notice). In Bungee Jumping of Their Own he excels, drawing laughs, respect and fear from his viewers in turn. Actress Lee Eun-ju is also outstanding in her smaller role, with her words and manner establishing the young couple's relationship as the key event of their lives.

The ultimate question for this work is whether it all holds together, as it unites a myriad of clashing moods and themes. At times it feels uneven, like it tried to cover too much ground, but the originality of this film will ensure that viewers do not soon forget it. (Darcy Paquet)

Last Present is a tragic romance so manipulative that you can almost hear its cogwheels and pulleys clicking and whirring like a well-oiled machine. Lee Jung-jae (Les Insurges, Last Witness) plays a two-bit gagman (as a stand-up comic is known in Korea, although what the gagmen do in this film is closer to vaudeville act, more Laurel and Hardy than Robin Williams) Yong-gi, whose marriage to Jeong-yeon (Lee Young-ae of JSA and One Fine Spring Day) is falling apart. A leaf is turned when he accidentally finds out that Jeong-yeon is dying from an unspecified incurable disease. Yong-gi, initially devastated, makes a resolution to win the TV gag contest at all costs, all the while hiding the fact that he is privy to his wife's secret. Intertwined with this sappy disease-of-the-month narrative are dollops of sepia-toned flashbacks concerning Jeong-yeon's object of childhood crush: Gee, who was that cute boy that had stolen her heart in the elementary school? As Linus Van Pelt once claimed, sugar cubes doused with honey can be a delicacy. But they are better served with a pinch of cinnamon, of course. Uwek...

I readily concede that Last Present may be as effective as a canister of tear gas in delivering "three-hankie moments" for many viewers. Even its sub-O. Henry plot contrivances are unflinchingly presented, without embarrassment. In fact, I suspect that the filmmakers, especially newcomer director O Ki-hwan, self-reflectively indicate their awareness of the movie's shameless melodramatics in the climactic gag sketch, in which the protagonist is seen squeezing his tear-drenched handkerchief like a wet towel. Last Present is by no means an artistic triumph of any kind and I would hesitate to even call it a good movie, but it is professionally put together, fulfilling the audience expectations to a tee.

I readily concede that Last Present may be as effective as a canister of tear gas in delivering "three-hankie moments" for many viewers. Even its sub-O. Henry plot contrivances are unflinchingly presented, without embarrassment. In fact, I suspect that the filmmakers, especially newcomer director O Ki-hwan, self-reflectively indicate their awareness of the movie's shameless melodramatics in the climactic gag sketch, in which the protagonist is seen squeezing his tear-drenched handkerchief like a wet towel. Last Present is by no means an artistic triumph of any kind and I would hesitate to even call it a good movie, but it is professionally put together, fulfilling the audience expectations to a tee.

I might have felt more charitable if the pairing of Lee Jung-jae and Lee Young-ae worked out better. I personally do not think Last Present's characters play to their strengths. Lee Jung-jae is not really convincing as an aspiring comic, and has trouble conveying the Chaplinesque "tears behind the smile" quality demanded by the role. (Not that he gets much help from the screenplay)

As for Lee Young-ae, even without any facial makeup, wrapped in dumpy housewife clothes, she stands out like a flawed emerald among rows of huge, immaculately shining glass beads. At the risk of sounding politically incorrect, I must point out that Lee is simply too beautiful: her beauty overwhelms the tritely conventional character she is stuck with. Instead of feeling sorry for Joeng-yeon, I was feeling sorry for Lee Young-ae the actress, bending backwards, nay, contorting herself, in order to play an "ordinary" woman. I mean, what's the point? The great Japanese director Ozu Yasujiro was once criticized for repeatedly casting the radiant Hara Setsuko as an "ordinary housewife:" the critics complained that no actual Japanese housewife could possibly look as glamorous and exotic as Hara. Ozu's response was to the effect that a director should be able to use the personality and looks of an actor to create a character, going beyond simplistic "realism," and that's what he has done with Hara. Ergo, it is possible for Lee Young-ae to be convincing in a role like Jeong-yeon. I just think that it might take more than a good performance on her part.

In the end, the main pleasure of Last Present for me remains its solid supporting cast. Failan's Kong Hyeong-jin is woefully underused but still leaves a favorable impression as Yong-gi's long-suffering stand-up partner. Veteran bit players Kwon Hae-hyo and Yi Mu-hyeon (instantly recognizable faces from many, many movies, even if you cannot remember their names) are hilarious and believable as two entertainment-industry con artists: I would have loved to see their characters expanded. Finally, the single most moving scene in the whole movie for me was the bittersweet reunion between Jeong-yeon and her high school best friend, Ae-suk, played with restraint and skill by Ku Hye-ryeong. This small scene has the aura of truthfulness that is rather lacking in other portions of this slick but artificial tear-jerker. (Kyu Hyun Kim)

You could hear the rumbling several weeks before it was released, and then when Friend hit the screens, it lived up to its hype. Four high school students in 1970s Pusan form an inseparable group of friends, despite their differing backgrounds. Years pass, however, and fate and violence combine to drive the four apart and test their friendship.

Director Kwak Kyung-taek's voice trembles when talking about this, his third feature, and it's little wonder why: Friend is a true story based on the lives of his three childhood friends (the role of Sang-taek, the wealthier member of the group who goes to study abroad, represents the director himself). Although the tragic story seems in some ways made for the screen, very little was altered in its telling. But it's not so much the story that distinguishes this film, but rather the feeling with which it is presented.

Director Kwak Kyung-taek's voice trembles when talking about this, his third feature, and it's little wonder why: Friend is a true story based on the lives of his three childhood friends (the role of Sang-taek, the wealthier member of the group who goes to study abroad, represents the director himself). Although the tragic story seems in some ways made for the screen, very little was altered in its telling. But it's not so much the story that distinguishes this film, but rather the feeling with which it is presented.

One major aspect of this movie's power is its cinematography. This has to be one of the most gorgeous Korean films of recent years, from cityscapes that resemble watercolors to the graceful shattering of windows and doors. Director of photography Hwang Ki-seok, a relative newcomer to the film scene, should take pride in the work he has created.

Actor Yoo Oh-sung has been distinguishing himself for several years with remarkable if largely unheralded performances, but this is clearly his breakout film. His acting dominates the movie, despite fine performances from supporting actors and his popular co-star Chang Dong-gun. Yoo shows an impressive range of emotions in his portrayal, but he also leaves a great deal unsaid, making for a complex portrayal that begs a second viewing.

Apart from creating this testament to his friends' experiences, Kwak has also forged a vivid portrait of his native Pusan. From the heavily accented Kyongsang dialect to elegant shots of its harbor, Korea's second-largest city is presented here in rare beauty. Although made famous by its international film festival, Pusan has seldom been presented on screen, making this film feel even more like an urgent, exciting discovery. (Darcy Paquet)

The (quasi-)melodrama Failan made a quiet debut at the end of April, opposite Hollywood blockbusters Hannibal and The Mexican. Audience interest was moderate at first, but with time the film acquired a strong group of admirers and people began to talk about one of the most original films of the year. With interest from overseas festivals running high and the star power provided by its female lead, this film is likely to travel far.

Lately an increasing number of Chinese and Japanese stars have signed on to act in Korean films. In Failan, Hong Kong top star Cecilia Cheung plays a Chinese woman of Korean descent named Failan who, after the death of her parents, comes to Korea to make a living. She pays for a fake marriage in order to obtain a working permit, but is then led unwitting into a bar to work as a prostitute. Only by some quick thinking is she able to escape her situation and find a job at a laundromat run by an old woman.

Lately an increasing number of Chinese and Japanese stars have signed on to act in Korean films. In Failan, Hong Kong top star Cecilia Cheung plays a Chinese woman of Korean descent named Failan who, after the death of her parents, comes to Korea to make a living. She pays for a fake marriage in order to obtain a working permit, but is then led unwitting into a bar to work as a prostitute. Only by some quick thinking is she able to escape her situation and find a job at a laundromat run by an old woman.

Meanwhile her legal husband, a third-rate gangster played by Choi Min-shik (Shiri, Happy End), is embroiled in troubles of his own. He dreams of returning to his hometown, but feuds with fellow gang members as his life increasingly nears collapse. One day he receives a letter written in halting Korean from his wife, whom he has never met.

Watching this film develop is in some ways like discovering a diamond in the trash. The story reveals for us emotions which we don't expect, but the film is not "uplifting" in the usual sense. Rather it makes us question feelings which we take for granted.

Director Song Hae-sung seems to have found himself in his second feature. His directing style never overshadows the film, but it provides space for this remarkable story to develop. He also makes excellent use of Choi Min-shik, perhaps the most talented actor in Korea today. Unfortunately Cecilia Cheung's character is not presented with the same depth; this is the film's main fault, perhaps attributable as much to the screenwriters and director as to the actress herself. Nonetheless Failan is one of the year's must-sees, and a personal favorite. (Darcy Paquet)

The 1999 film Attack the Gas Station surprised everyone with its runaway popularity, drawing mobs of viewers despite its low budget and simple premise. In 2001, the team behind this film tried to duplicate their level of success with this next feature, and unexpectedly, that's just what they did. At the time of this writing, Kick the Moon was the fourth best-selling Korean film of all time.

The film stars Lee Sung-jae and Cha Seung-won as two former high-school classmates who grow up into unexpected professions: Lee, the smart kid in school, becomes a gangster; while Cha, the school bully, decides to be a physical education teacher (perhaps that one wasn't quite as unexpected). Relations between the two had always had an edge of competitiveness, but when they run into each other years later in the city of Gyeongju, they try to put old rivalries aside for a friendly reunion. All this changes, however, when they meet the outspoken owner of a local restaurant, played by popular actress and model Kim Hye-soo. Kim's earthy appeal sets both their hearts aflame, and their latent competitiveness soon transforms into insults, threats, and full-scale street warfare.

The film stars Lee Sung-jae and Cha Seung-won as two former high-school classmates who grow up into unexpected professions: Lee, the smart kid in school, becomes a gangster; while Cha, the school bully, decides to be a physical education teacher (perhaps that one wasn't quite as unexpected). Relations between the two had always had an edge of competitiveness, but when they run into each other years later in the city of Gyeongju, they try to put old rivalries aside for a friendly reunion. All this changes, however, when they meet the outspoken owner of a local restaurant, played by popular actress and model Kim Hye-soo. Kim's earthy appeal sets both their hearts aflame, and their latent competitiveness soon transforms into insults, threats, and full-scale street warfare.

As in their previous feature, director Kim Sang-jin and producer Kim Mi-hee (one of Korea's top trio of female producers) employ violence, hyperbole, and struggles for power to drive their film forward. Kick the Moon also contains its share of well-drawn characters. Cha as the slightly obsessed gym teacher makes the biggest impression, first terrorizing his students and then battling to win over Kim. Strangely enough, the gangster played by Lee comes across as the film's most sensible and admirable character. Kim Hye-soo, in her return to the screen after an absence of several years, seems perfectly cast as the spirited woman who sets both men's hearts reeling.

Perhaps the biggest difference between this film and its predecessor is in its setting. Attack the Gas Station made do with a remarkably limited set, while Kick the Moon sprawls amidst the rural city of Gyeongju, a popular tourist site and the old capital of the Shilla Dynasty. The expansive set gives the film a unique look, but at the same time makes for a somewhat chaotic viewing experience. Scores of characters add to this feeling, as if the plot had gone slightly out of control.

This need not be a bad thing; viewers who liked Attack the Gas Station will surely enjoy the twists and lumps this new film dishes out. Personally, however, I found myself missing the simplicity and charm of the first film. (Darcy Paquet)

Comedies have dominated the summer and early fall of 2001, with a trio of smash hits that have easily outgrossed every Hollywood film to get a release. Among these, my personal favorite is My Sassy Girl, a movie based on a series of real-life incidents published on the internet in serial form.

As the film opens we are introduced to Kyun-woo, a kind-hearted but at times naive college student who seems to keep getting into trouble. On his way home one night he encounters a beautiful but completely smashed young woman who causes a scene in the subway, calls him "honey", and then passes out. With the eyes of the other subway passengers upon him, he has little choice but to take responsibility for her. Thus begins his relationship with the at-times charming, at-times violent damsel who steals his heart.

As the film opens we are introduced to Kyun-woo, a kind-hearted but at times naive college student who seems to keep getting into trouble. On his way home one night he encounters a beautiful but completely smashed young woman who causes a scene in the subway, calls him "honey", and then passes out. With the eyes of the other subway passengers upon him, he has little choice but to take responsibility for her. Thus begins his relationship with the at-times charming, at-times violent damsel who steals his heart.

Much of the film is structured around the bizarre antics of Kyun-woo's newfound girlfriend. After she passes out yet again, Kyun-woo looks at her blissful face and promises to himself that he will save her, and right whatever it is that troubles her. This proves to be much more of a challenge than he expects.

My Sassy Girl marks the return to the screen of director Kwak Jae-yong, after close to a seven-year absence. He couldn't have picked a better film for his comeback, and he is unlikely to be away for so long again: in October he signed a contract to make three more films in the next six years.

Cha Tae-hyun, who plays Kyun-woo, has been a well-known personality on TV shows, advertisements, and also as a successful pop singer, but this is his first major role in the movies. He proves perfect for the part, his blend of mischievous innocence capturing the audience's sympathies. The undisputed star of this film, however, is Jeon Ji-hyun, an icon for her generation who trades in the nice girl image of her previous films for something with a little more fire. The enthusiasm she brings to the role carries the film; it could not have succeeded anywhere near as well without her.

The wacky charms of this film have earned it the title of Korea's best-selling comedy ever (at least for the moment). In the coming months, as the film spreads to other countries in Asia and possibly to DVD, foreign audiences will get a chance to share in the fun. (Darcy Paquet)

Korea produced only two horror films in 2001, nonetheless the genre was pushed in new directions by the eerie debut film Sorum. Premiering at the Puchon Fantastic Film Festival in July, the film was embraced by local critics and credited with giving the industry one of its strongest works of the year.

More creepy than scary, the movie tells the story of a young taxi driver who moves into a dilapidated old apartment building. Soon thereafter he befriends one of his neighbors, a woman who is beaten by her husband, and hears from another neighbor of the strange history behind the room he has moved into.

More creepy than scary, the movie tells the story of a young taxi driver who moves into a dilapidated old apartment building. Soon thereafter he befriends one of his neighbors, a woman who is beaten by her husband, and hears from another neighbor of the strange history behind the room he has moved into.

Director Yoon Jong-chan had already made a name for himself in the industry with the inventive short films he directed while a student at Syracuse. Yoon's short films like Playback and Memento, helpfully included in Sorum's initial DVD release, provide stylistic and thematic links to his debut work. Yoon's interest in personal history, together with the unsettling mood he creates, makes for a memorable watch.

Despite being a somewhat grim movie, visually Sorum is one of the most gorgeous films of the year. The apartment building where much of the story takes place is so dilapidated and grim that it resembles a work of art. Yoon also put great care into his low-key lighting, creating subtle colors and shadows which are beautiful to watch.

The film's actors have received much praise, particularly Chang Jin-young for her raw portrait of a woman racked with loss and guilt. In December she received the Blue Dragon award for the best actress of the year.

This isn't a film that everyone will enjoy; in some ways it's more suited for people who don't like horror films. Yet the film's mood and artistic sensibilities make it one of the year's most interesting movies. (Darcy Paquet)

None of the films released in 2001 has matched the hype and expectation of Musa, a period epic set in 14th-century China. The film's plot is based on real history: shortly after the Ming Dynasty seized power in China, a Ming envoy to Korea was murdered, leading to soured relations between the two countries. In efforts to mend ties, Korea sent numerous envoys to China, but most were simply thrown in jail by the Ming. Musa is the story of a group of envoys sent to China who are arrested and then sent into exile. Off in the wilderness they manage to rescue a Ming princess, and they hope that if they can return her to the Ming safely, their honor and good relations between the two countries will be restored.

The film features both a well-known director in Kim Sung-soo (Beat) and a star cast: heartthrob Jung Woo-sung as a spear-wielding slave, Joo Jin-mo as the young general, Ahn Sung-ki as a lower-class fighter, and Chinese actress Zhang Ziyi from Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon as the Ming princess. Zhang was reportedly cast before Crouching Tiger premiered at Cannes in 2000, a lucky break for the makers of the film. Although her role in Musa features none of the martial-arts stunts for which she has since become famous, her presence on the cast has raised the international profile of this film considerably.

The film features both a well-known director in Kim Sung-soo (Beat) and a star cast: heartthrob Jung Woo-sung as a spear-wielding slave, Joo Jin-mo as the young general, Ahn Sung-ki as a lower-class fighter, and Chinese actress Zhang Ziyi from Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon as the Ming princess. Zhang was reportedly cast before Crouching Tiger premiered at Cannes in 2000, a lucky break for the makers of the film. Although her role in Musa features none of the martial-arts stunts for which she has since become famous, her presence on the cast has raised the international profile of this film considerably.

Musa is darker in mood than most blockbusters, with a brutality that leaves little room for romanticism. The director has said that he tried to present his story in the most realistic way possible. This can be seen in the film's impressive fight scenes, which leave the viewer feeling like an unlucky warrior caught amidst the battle. Apart from the disorienting rush of noise and images, the violence is also startling: severed limbs and arrows shot through victim's necks drive home the cruelty of battle.

The story itself is also somewhat unusual for big-budget films. The movie's characters are not your typical heroes: most have an ugly streak which flares up under the extreme situations they face. As the story progresses, power relations among the group are constantly in flux, as the young general and princess gradually start to lose influence among their followers.

The film has some flaws, due in part to its vast ambition. Weak storytelling at the beginning makes it difficult to follow the story or to feel much sympathy for the characters initially. The acting is mostly strong but uneven in parts. Fans of Zhang Ziyi, accustomed to seeing her pound her opponents into submission, may also feel disappointed with the passive character of the princess, although her performance fits in well with the themes of the film.

Undisputed, however, is the strength of Musa's visuals. Shot in 2.35:1 Cinemascope, the film cuts between stunning landscapes and extreme closeups in a restless, uneven rhythm. Adding to the cinematic thrill is the film's epic score by Japanese composer Shiro Sagisu. Those looking for a bit of widescreen, gory spectacle this fall are advised not to miss this film. (Darcy Paquet)

The 1998 melodrama Christmas in August left a big impression on the Korean film industry. With its subdued tone and understated themes, the film in many ways upended the way Korean filmmakers approach melodrama. Director Hur Jin-ho won over fans both in Korea and in the rest of Asia for his ability to infuse everyday situations with emotion and meaning.

For his second film, Hur chose a universal and somewhat ordinary subject: a man and a woman who fall in love, and then break up. He says that while his first film was structured around the beginnings of love, One Fine Spring Day is more concerned with how it ends. As with his previous film, families play an important role: the man, Sang-woo, lives with his father, aunt, and grandmother, relying at times on their support; Eun-su, the woman, lives alone.

For his second film, Hur chose a universal and somewhat ordinary subject: a man and a woman who fall in love, and then break up. He says that while his first film was structured around the beginnings of love, One Fine Spring Day is more concerned with how it ends. As with his previous film, families play an important role: the man, Sang-woo, lives with his father, aunt, and grandmother, relying at times on their support; Eun-su, the woman, lives alone.

One Fine Spring Day is a gorgeous film that will bore some viewers and captivate others. Hur has sometimes been called "Korea's Ozu" for his slow pacing and introspective style (he himself is a big fan of the Japanese director). Yet to make this comparison may be silly, and at any rate Hur's works are infused with his own personality. With only two films he has become an important voice in Korean cinema, and his twisting of melodrama to make it serve different ends has inspired many young Korean filmmakers.

One thing that makes this film particularly special is its use of sound. The characters themselves are drawn together by sounds (Sang-woo is a recording engineer, Eun-su is a radio producer), but everyday sounds, both man-made and natural, make up a crucial aspect of the film's style. When combined with precise and at times striking camerawork, the film is able to create moments that are both solemn and beautiful to see. It's unfortunate, then, that the film's musical soundtrack, which lacks the subtlety of the work as a whole, often intrudes into the stillness. This is clearly the film's biggest weakness.

The film's stars, Yoo Ji-tae and Lee Young-ae, earned both praise and new respect from local critics after the film's opening. Both are popular new actors who are just coming into their own, which makes them particularly appropriate for the roles of a young couple who are struggling to understand how they feel about each other.

Anyone who has been through a painful breakup will likely find resonance in the situations depicted by this film; part of this film's strength is its universality. Yet what makes the movie so enduring is its specifics: its seemingly offhand gestures and memorable bits of dialogue that give the characters such depth and color. (Darcy Paquet)

Following in the footsteps of the runaway success of Friend, My Wife is a Gangster flexed her muscles at the box office of 2001, raking in more than five million tickets nationwide. Unlike Friend, however, My Wife was met with an almost universal hostility by critics and is intensely disliked by many viewers as well (It was the "winner" of the 2001 Ready-Stop Award given to the worst Korean movie of the year).

The story is certainly not a Yi Sang Literary Award material. Eun Jin (Shin Eun-kyung) is a female gangster who uses a pair of wicked-looking scissors as her weapon of choice. In order to please her terminally ill sister, Eun Jin declares that she needs a husband pronto, driving her lieutenants, Majinga (Shim Won-chul), a silent type who has a metal plate embedded in his skull, and Butter (An Jae-mo), an orange-haired, smarmy Don Juan, into distraction. After a few disastrous attempts, she lassoes in Soo Il (Park Sang-myun), a proper-mannered, starry-eyed government clerk, for a quick ceremony. A TV drama-style domestic comedy ensues, which involves quite a few bits of cringe-inducing "clever" dialogue. (The movie's biggest weakness in my view)

The story is certainly not a Yi Sang Literary Award material. Eun Jin (Shin Eun-kyung) is a female gangster who uses a pair of wicked-looking scissors as her weapon of choice. In order to please her terminally ill sister, Eun Jin declares that she needs a husband pronto, driving her lieutenants, Majinga (Shim Won-chul), a silent type who has a metal plate embedded in his skull, and Butter (An Jae-mo), an orange-haired, smarmy Don Juan, into distraction. After a few disastrous attempts, she lassoes in Soo Il (Park Sang-myun), a proper-mannered, starry-eyed government clerk, for a quick ceremony. A TV drama-style domestic comedy ensues, which involves quite a few bits of cringe-inducing "clever" dialogue. (The movie's biggest weakness in my view)

The gangster-movie plot picks up in the latter half, as now-pregnant Eun Jin and her cronies are attacked by the rival gang, White Sharks, resulting in a series of exciting fight scenes and a fiery climax (possibly inspired by the James Bond film Licence to Kill) in which the formerly pacifistic Soo Il avenges his hospitalized wife and gains a legendary status among the gangsters. Thankfully, the movie does not slide into a mawkish, "serious" tone that marred many recent Korean comedies, and stays true to its comic-pulp roots to the very end. (One indication of how completely the world of My Wife is removed from reality is that not a single policeman shows up, in a movie filled to the brim with gangsters, prostitutes and truckloads of deadly weapons of assault)

Considering that the film has little aspiration to any form of artistry or meaningfulness, its technical achievements are rather impressive. The cinematography, helmed by the super-veteran Jung Jo-myung, responsible for Seaside Village (1965), Eternal Empire (1995) and A Promise (1998), generally stresses wild, primary colors but also exacts gentle, subdued hues from quieter scenes. The action choreography, while not original, is above the par for a Korean film. The best action sequence, a duel between Eun Jin and a White Shark assassin set in a field of reeds, appears to be an hommage to Kurosawa Akira's debut film Sanshiro Sugata (1945).

Like Friend and Hi, Dharma, My Wife benefits enormously from good casting. Park Sang-myun again proves his worth as one of the top supporting players in contemporary Korean cinema. He is given the difficult job of playing a straight man to the movie's colorful, larger-than-life characters. His deadpan reaction gives a firm center to the film. An Jae-mo (one of my favorite Korean actors, yet to fully realize his potential) and Shim Won-chul provide able supports: I especially liked the interactions between An Jae-mo's Butter and his main "squeeze," Seri (Choe Eun-joo).

My Wife is a Gangster in many ways deserves its infamy: it is a bloated, ludicrous, in-your-face blockbuster, rather like a half-pound hamburger, grilled in sizzling animal fat, and served with thickets of French fries and a beer mug full of Jolt Cola. At the same time, I cannot deny its sheer entertainment value. It is even possible to appreciate the care and professionalism that went into the final product (the movie does make me look forward to the director Jo Jin-gyu's next project)--it's just that you should not expect anything really nutritious. (Kyu Hyun Kim)

It's exciting to see a small picture elbow its way into the spotlight every so often. Despite its minimal budget and lack of established stars, Nabi has captured notice with invitations to several high-profile festivals and a pair of best actress awards. It certainly deserves the attention; this beautiful and strange film offers its viewers a memorable experience.

Nabi is set in the not-too distant future, in a Korea which looks only vaguely familiar. Acid rain and lead poisoning have created new dangers for the population, while the outbreak of a mysterious virus has perversely resulted in a new tourist industry. This so-called Oblivion Virus causes no physical harm, but it erases the memory of its victims. Henceforth a wave of 'tourists' begins to flow into the country; people suffering from awful memories, hoping to start their lives over.

Nabi is set in the not-too distant future, in a Korea which looks only vaguely familiar. Acid rain and lead poisoning have created new dangers for the population, while the outbreak of a mysterious virus has perversely resulted in a new tourist industry. This so-called Oblivion Virus causes no physical harm, but it erases the memory of its victims. Henceforth a wave of 'tourists' begins to flow into the country; people suffering from awful memories, hoping to start their lives over.

Anna Kim is one of these travelers; the film charts her return to Korea after living in Germany most of her life. Rather than emphasize her search for the virus, the film concentrates on the relationship she develops with her guide -- a teenage girl -- and her driver. The time she spends with them changes her, leading her down paths she wasn't expecting.

Nabi's director, Moon Seung-wook, studied at the Poland National Film School at Lodz and made his debut in 1998 with a little-watched film titled Taekwondo, shot in Poland and starring Ahn Sung-ki. In Nabi he creates a dark and vivid world using creative lighting, disjointed editing and hand-held digital video. Perhaps his biggest accomplishment is the performance he draws out of his cast. Actress Kim Ho-jung acted previously as the wife in Barking Dogs Never Bite, and her heartbreaking performance here won her a Best Actress award from the Locarno Film Festival in Switzerland. Kang Hae-jung, who plays the guide, also excels in her role, and she in turn won the Best Actress award at the Puchon Fantastic Film Festival in July.

Sometimes you feel that a film is getting at something elemental, if not in words, then in images. Nabi's strongest scenes portray for us people and emotions at their most basic level. Whether splashing in a pool or playing on a beach, the characters in this film seem to embody the core of what it is to be human. (Darcy Paquet)

Jang Jin's Guns & Talks juggles genres as so many mainstream Korean films do. Part cop actioner, part drama, part comedy, the film even drops in moments of art film aesthetics, such as the tryptyching-ing when Detective Cho (Jeong Jin-young) violates legal procedures in his warrant-less search of the home of our assassins or the slow, horizontal sliding of silenced frames of our four assassins standing within an outdoor Greek-style amphitheatre to a dreamy, breathy, blue-tinted flashback of the meeting between Sang-yun (Shin Hyun-jun) and their surprise client. The film reaches its peak during a wonderful hit at the Seoul opera house that makes the viewer want to stand up and applaud and bravo-bravo just like the opera's audience. This scene works on so many levels, with the added pleasure of the professional set design and quality performance samples of Sheakespeare's Hamlet. We all know South Korean film has come into its own, this scene just underscores that and hints that South Korean theater production may have reached a level of high quality as well.

But upon leaving this powerful scene, what follows doesn't live up. And when you look back at the previous scenes, neither do they. The film as a whole does not represent the parts of its sum that are the opera house scenes. There are pleasurable moments of style, such as the bullet time first hit, or humorous moments, such as Jung-woo (Shin Ha-kyun) perpetrating as if he's the next door neighbor of the hit he strikes out on rather than strikes upon. And the abrupt shift from the humorous predicament of Sang-yun struggling to improvise his way around a hit gone minutely, yet importantly, wrong, to the poignancy of Ha-yun (Won Bin) sharpshooting into adulthood resonates as perfectly as the post-gunfire aural reverberations. But, afterwards, further supporting my point, this scene is tainted by the less than fully utilized scene that follows between big and little brother. The film doesn't follow the bullet time flow. Rather, we have something more like gunfire splaying in different directions, occasionally hitting its target soundly.

But upon leaving this powerful scene, what follows doesn't live up. And when you look back at the previous scenes, neither do they. The film as a whole does not represent the parts of its sum that are the opera house scenes. There are pleasurable moments of style, such as the bullet time first hit, or humorous moments, such as Jung-woo (Shin Ha-kyun) perpetrating as if he's the next door neighbor of the hit he strikes out on rather than strikes upon. And the abrupt shift from the humorous predicament of Sang-yun struggling to improvise his way around a hit gone minutely, yet importantly, wrong, to the poignancy of Ha-yun (Won Bin) sharpshooting into adulthood resonates as perfectly as the post-gunfire aural reverberations. But, afterwards, further supporting my point, this scene is tainted by the less than fully utilized scene that follows between big and little brother. The film doesn't follow the bullet time flow. Rather, we have something more like gunfire splaying in different directions, occasionally hitting its target soundly.

Our four assassins do step out somewhat from their cookie-cutter frames. Jae-young (Jeong Jae-yeong) is the most talkative of silent types, Jung-woo the least irritable of hot-headed gangsters, Ha-yun the least innocent of young knaves, and Sang-yun, . . . well, with the amount of eye-liner he's cast to wear, his character could have been taken in any number of interesting discursive directions, but, instead, he falls into a reasonably contained leadership role without too much obnoxious authoritarian command.

Still, there are jagged edges that never fit into each character's piece of the plot puzzle. Jae-young's attendance at confession is never used after it's noted in Ha-yun's beginning narration when such could have allowed for interesting plot extensions. Sang-yun's need to take pictures of each of their clients is a practical clarion call for the cops to catch him. Plus, the subplot involving actress Gong Hyo-jin, although intended, along with Jung-woo's "failed" hit, to demonstrate the human/moral side of these assassins, ends on a humorous note much too quickly. And then Gong just shows up at the end sans any further development of her character and her relation to Ha-yun. Just as Ha-yun's narration stumbles in the middle of the film, much of Guns & Talks does as well.

If only what happened before the Shakespeare scene were a true build up to the height reached at that moment, and if only the film had somehow wrapped up the ending then, would more talks about this film be warranted. (Adam Hartzell)

"Koreans don't like cats," says director Jeong Jae-eun. "Cats are fussy, independent, and don't listen to what you tell them. If they don't like their home, they simply leave." For Jeong, an avid cat lover, the animals are also a fitting symbol for the vitality and attitude of Korea's young women. Take Care of My Cat tells the story of such women (and their cat) with a freshness and originality that places it among the best films of the year.

Take Care of My Cat is the first film directed by a Korean woman to be released in close to three years. Although a large number of women directors are poised to debut in the near future, this is nonetheless an indication of how male voices have continued to dominate Korean cinema. "There have been no movies in the past that have depicted well how young Korean women think, how they play and what they worry about," says the director. "I hope that this film can give audiences a sense of what young Korean women are like and how beautiful they are."

Take Care of My Cat is the first film directed by a Korean woman to be released in close to three years. Although a large number of women directors are poised to debut in the near future, this is nonetheless an indication of how male voices have continued to dominate Korean cinema. "There have been no movies in the past that have depicted well how young Korean women think, how they play and what they worry about," says the director. "I hope that this film can give audiences a sense of what young Korean women are like and how beautiful they are."

The film tells the story of five women who are just beginning their lives after graduating from high school. Each of the women face different challenges, be it family or money, but they are united in their need to try new things and to be taken seriously. The plot traces several stories at once, but highlights the conflicts its protagonists face both among themselves and with a society that largely overlooks them.

One of the most exciting aspects of this film is the new talent it highlights. This is the first feature film by director Jeong Jae-eun, following a string of award-winning short films. This movie will hopefully be only the start of a long and interesting career. Many of the actors in the film are rising stars as well, particularly Bae Doona (poised perhaps to break out into a major star in 2002) and Lee Yo-won.

This movie seems to get on the inside of what it is like to be young. From its ultra-cool soundtrack to its clever use of text messaging, the film is filled with memorable details that remain long in the viewer's memory. (Darcy Paquet)

It took nearly five years for Director Im Sun-rye to return to feature film since her brilliant Three Friends (1996). For anyone who appreciates Korean cinema, the long wait was worth it. Waikiki Brothers was, like Take Care of My Cat, largely ignored in its initial release, but has since developed a very loyal fan base, mostly out of strong word of mouth.

The film chronicles the fate of a shoddy nightclub band named, as you may have guessed, Waikiki Brothers. As it opens, the lead vocal Sung-woo (Lee Uhl), having run out of other options, reluctantly signs a contract with a hotel in his hometown Suanbo, a washed-up resort town, once famous for its hot springs. Along with him for the ride are a bear-like, soft-hearted drummer Kang-soo (Whang Jeong-min) and a lecherous keyboardist Jong-suk (Pak Won-sang). However, Sung-woo's plan for a fresh start is compromised by Kang-soo's addiction to gambling and drugs and Jong-suk's compulsive womanizing. Meanwhile, Sung-woo runs into his old schoolmates, who used to play together in their high school rock band (from which the current band's moniker originated), and the object of his teenage crush, Inhee (Oh Ji-hye). For Sung-woo, these encounters, instead of evoking nostalgia for good old times, serve as rather bitter reminders of the ravages of time, and how becoming an adult means paying the price of having to forget the carefree pleasure of making music.

The film chronicles the fate of a shoddy nightclub band named, as you may have guessed, Waikiki Brothers. As it opens, the lead vocal Sung-woo (Lee Uhl), having run out of other options, reluctantly signs a contract with a hotel in his hometown Suanbo, a washed-up resort town, once famous for its hot springs. Along with him for the ride are a bear-like, soft-hearted drummer Kang-soo (Whang Jeong-min) and a lecherous keyboardist Jong-suk (Pak Won-sang). However, Sung-woo's plan for a fresh start is compromised by Kang-soo's addiction to gambling and drugs and Jong-suk's compulsive womanizing. Meanwhile, Sung-woo runs into his old schoolmates, who used to play together in their high school rock band (from which the current band's moniker originated), and the object of his teenage crush, Inhee (Oh Ji-hye). For Sung-woo, these encounters, instead of evoking nostalgia for good old times, serve as rather bitter reminders of the ravages of time, and how becoming an adult means paying the price of having to forget the carefree pleasure of making music.

Im Sun-rye's directorial style may initially strike you as old-fashioned naturalism. She keeps most of her compositions in middle or long distance: there are hardly any close-ups. Any type of technical razzle-dazzle that calls attention to itself -- even jump cuts or interesting color schemes -- has been rigorously excluded. The only flight of fancy she allows is the insertion of Sung-woo's flashback of the naked frolic with his high school buddies into the karaoke video played during the "orgy" sequence. And yet, her "distancing" narrative strategy does not result in the loss of empathy. We are denied voyeuristic pleasure, but we never lose intimate relationships with the characters.

Waikiki Brothers is not lugubrious. It has its funny moments, although none of it is overtly "comedic." During the screening I attended, the sequence where Kang-soo, now a bus driver, begins to uncontrollably weep while berating his erstwhile bandmate brought down the house. The humor rises out of the recognizable absurdity of the situation, not out of any calculated strategy to tickle the viewer's funnybone. On the other hand, without making any fuss, Im allows us to glimpse into the all-too-real suffering and sheer despair of the characters. For instance, Kim Kyung-ho as Sung-woo's guitar instructor presents one of the most convincing and harrowing portrayals of an alcoholic I have seen in any movie. When Sung-woo's former schoolmate (Shin Hyun-jong), fired from the city office job and suicidally depressed, asks him, "Are you happy? You are the only one who is doing what you wanted," the statement is like a stab in the heart. In the end, though, Im wraps up the film with a cautiously optimistic ending that seems to vindicate Sung-woo's dogged commitment to performing music. The movie is mostly cast with relatively unknown theatrical actors, but the acting is for the most part excellent. I only learned later that many small but not insignificant roles in the movie were in fact filled with non-actors: they blend seamlessly with professional thespians. Even Ryu Seung-beom, the only acknowledged "star" in the cast, plays a relatively subdued character, whose story arc has a witty, so-this-is-the-generation-gap-in-Korea resolution.

Waikiki Brothers is a tough, restrained but ultimately compassionate film that you may wish to revisit many times, to relish its flavor that, like good wine, gets better with repeated viewings. (Kyu Hyun Kim)

The last part of 2001 was more or less dominated by a single genre: the gangster comedy. Following the booming success of Kick the Moon in the summer, three more stories about gangsters went on to seize hold of the box-office: My Wife is a Gangster, Hi Dharma, and My Boss My Hero. My personal choice among this rowdy quartet is Hi, Dharma, a story about gangsters and monks.

Hi, Dharma starts in rather unremarkable fashion, portraying an escalating gang war that ultimately sends one group of thugs into hiding. As they drive off into the countryside, it dawns on them that a Buddhist monastery would make the ideal hiding place. They arrive at the monastery with loud threats and fist-waving, and as they don robes and settle in, their obnoxious behavior begins to wear on the monks. Finally tempers start to flare, and the monks reveal they have a surprise or two in store for their guests.

Hi, Dharma starts in rather unremarkable fashion, portraying an escalating gang war that ultimately sends one group of thugs into hiding. As they drive off into the countryside, it dawns on them that a Buddhist monastery would make the ideal hiding place. They arrive at the monastery with loud threats and fist-waving, and as they don robes and settle in, their obnoxious behavior begins to wear on the monks. Finally tempers start to flare, and the monks reveal they have a surprise or two in store for their guests.

Director Park Chul-gwan makes a rather impressive debut with this film, telling his story simply but effectively, while drawing impressive performances from his ensemble cast. Although containing no real A-list stars, the movie features a strong group of actors who have taken a wide variety of roles in other films. Kim In-moon, in particular, is excellent as the elder monk, who tries to strike a balance between the two groups.

Many of Korea's gangster films claim to be critiques of organized crime, playfully poking fun at their leading characters' egos or lack of intelligence, but in truth most of them glorify the profession. Polls have shown that many schoolchildren have developed highly positive attitudes towards organized crime over the past couple years, presumably affected by popular media. One refreshing aspect of Hi, Dharma is the extent to which it tries to avoid this, providing solid entertainment while keeping the romanticism more or less in check. (Darcy Paquet)

There is nothing like a taboo to grab an audience's attention. One can choose to simply throw in some cannibalism or sado-masochism to shock or to titillate in ways extraneous to the plot or one can dare choose to empathize with the partners in a taboo, asking the audience to compare and contrast with what they see on the screen. Kim Yong-gyun has chosen the latter direction in his film Wanee and Junah. Wanee (Kim Hee-sun) and Junah (Joo Jin-mo) are live-in lovers whose relationship becomes emotionally distant as memories of Wanee's past surface. At the same time as Wanee wrestles with her past, Junah struggles to establish himself as a writer without sacrificing the art in his work in order to acquire his first film credit.

Brief reviews should rarely give away the secret of a film unless it is so obvious as not to be a real secret. In this case, I feel the subtle revelation of the primary taboo is too important to one's engagement with this film to risk revealing. So I will walk around it just as we walk around it in our mutual societies. Furthermore, surrounding the taboo that's name I dare not speak are many other taboos that should equally go unspoken because part of the pleasure in this film is pointing out each of them, either directly noted or merely hinted at. My roommate and I are still arguing about one, and until either of us learns Korean Sign Language, we'll never really know, since the DVD does not translate the deaf character's dialogue beyond her first scene with Wanee. One relationship taboo I can mention, and already have. That is, Wanee and Junah are an unmarried couple living together, something more accepted in Western cultures but still looked at disapprovingly in South Korea. Few of the taboos presented are judged, allowing for us to judge for ourselves how we feel about each. This wealth of transgressions of mythic norms appears to say that each of us at some moment in our lives crosses boundaries we are told to never cross, and it is for each of us to decide what boundaries are best to never cross. Some taboos are clearly wrong, others are more ambiguous, and, with still others, the statement that they are wrong is what's wrong. Rather than hold court, director Kim lets the audience as jury decide.

Brief reviews should rarely give away the secret of a film unless it is so obvious as not to be a real secret. In this case, I feel the subtle revelation of the primary taboo is too important to one's engagement with this film to risk revealing. So I will walk around it just as we walk around it in our mutual societies. Furthermore, surrounding the taboo that's name I dare not speak are many other taboos that should equally go unspoken because part of the pleasure in this film is pointing out each of them, either directly noted or merely hinted at. My roommate and I are still arguing about one, and until either of us learns Korean Sign Language, we'll never really know, since the DVD does not translate the deaf character's dialogue beyond her first scene with Wanee. One relationship taboo I can mention, and already have. That is, Wanee and Junah are an unmarried couple living together, something more accepted in Western cultures but still looked at disapprovingly in South Korea. Few of the taboos presented are judged, allowing for us to judge for ourselves how we feel about each. This wealth of transgressions of mythic norms appears to say that each of us at some moment in our lives crosses boundaries we are told to never cross, and it is for each of us to decide what boundaries are best to never cross. Some taboos are clearly wrong, others are more ambiguous, and, with still others, the statement that they are wrong is what's wrong. Rather than hold court, director Kim lets the audience as jury decide.

As much as I enjoy this film, there are moments that don't quite work for me. The direction of the employees of the animation studio where Wanee works results in scenes where their banter comes off way too scripted, their movements way too choreographed. Yes, most every fictional film is a series of set ups, of mise-en-scenes, but the performances are supposed to assist us in suspending our disbelief. (And, apparently, badminton is the official sport of all animation studios, for, just like at Pixar, they play it here.) Yet, other efforts to represent the life of an animator add to the film, such as the physical consequences of the work, signified by employees baring wrist braces and POV shots of Wanee's blurry vision.

Along with the POV shots, Kim Yong-gyun includes other editing elements that add depth to the story. Sounds will intrude a scene that could only logically be associated with the following scene, such as hearing water pouring from a faucet while Wanee and Junah are still in bed and then cutting to Wanee in the kitchen pouring water from the faucet. This technique provides precedence for later scenes when the present blends seamlessly into scenes from the past. An example is when we see Wanee at the dinner table of her adult years and the camera then pans to the living room of her high school years. At times Wanee's phone conversations often appear like apparitions, Junah will walk in without acknowledging who is there because we're actually inside Wanee's head, not really seeing what Junah sees. This is most striking when we first become aware of this, considering how rude it would be for Junah not to greet Wanee's mother. We learn she really isn't there in their living room, but on the phone with Wanee. And the endearing animation sequences which bookend the film, accompanied by a gorgeous score composed by Kim Hong-jib and Kang Min, add to the film while staying syntonic with the story.

Despite its problems in the feel of some scenes, Wanee and Junah is more than your average melodrama. Having taken on the taboo it does, it could have failed poorly in its execution. It could have just been a gratuitous effort to jar us or a redundant moral lecture. Kim Yong-gyun and the cast tastefully took on a difficult task. For the most part, it works, presenting an intriguing tale of letting go of our unhealthy pasts to accept the challenges before us whether we are rewarded for our mature, ethical decisions or not. (Adam Hartzell)

Having heard so much critical praise for Song Il-gon's recent films, Spider Forest (2004) and Git (2004), films I have yet to have the opportunity to see, I decided to revisit one of Song's films I do have access to, his debut feature, Flower Island. This film about three wounded women traveling South to an island with proclaimed magical powers failed to cast a spell on me initially so I figured I'd give it a second chance. The film begins by showing us the shocking wounds these women have experienced. One is self-inflicted, the other ambiguously acquired, and the other interpreted by the character as punishment from God. Ok-nam (Seo Joo-hee) is the self-inflicted. Feeling a need to acquire a piano for her daughter but unable to afford one, she sleeps with an elderly man who can provide her with this gift. Unfortunately, this man has a heart attack from the strain involved in the agreed upon transaction, sending Ok-nam to the police after which her husband sends her away temporarily as well. Hye-na's (Kim Hye-na -- Into the Mirror) wound is equally shocking. We discover she'd been hiding an unwanted pregnancy as we witness her giving birth alone in a random toilet somewhere. And, finally, Yoo-jin (Im Yoo-jin) has acquired a cancer through the harsh fate of statistical realities, but the cancer affects the very tool of her trade, her operatic singing voice. Ok-nam and Hye-na fall into each other's care after a trip they had separately planned South heads North. And it is within that Northern environ that they meet Yoo-jin who traveled up on her own to kill herself, an action the two other women abort.

Along their journey to a place where "you will forget all your sorrow and misery" -- a similar premise of a film of the same year, Moon Seung-wook's memory-eraser Nabi -- they acquire brief assistance from random men they meet along the way. The interactions with these men eventually reach a moment of discomfort, such as the disturbing words of the truck driver or the manic depression of a band member. (Song's choice to have this character, a sissified Korean, played by the same actor, Son Byong-ho, who plays Ok-nam's husband is a clever move, presenting strangers as only temporary strangers until we recollect whom they represent in our familiar orbit. Also, Song has made a nice ethical choice in coupling this Sissy character with a less stereotyped, Ska-influenced boyfriend so as not to leave us with the Sissy as the sole Queer representation within the film.) What is most striking about these discomforting interactions with men is that there is no striking. That is, no male violence upon women. There are moments where we'd almost expect violence, such as Ok-nam's shameful meeting with her husband at the police station, given the Korean film tropes that came before and after. But in most of these interactions, the men eventually offer non-patriarchal moments of concern and comfort towards the collective plight of these women, assisting them in their quest rather than restricting their movement.

Along their journey to a place where "you will forget all your sorrow and misery" -- a similar premise of a film of the same year, Moon Seung-wook's memory-eraser Nabi -- they acquire brief assistance from random men they meet along the way. The interactions with these men eventually reach a moment of discomfort, such as the disturbing words of the truck driver or the manic depression of a band member. (Song's choice to have this character, a sissified Korean, played by the same actor, Son Byong-ho, who plays Ok-nam's husband is a clever move, presenting strangers as only temporary strangers until we recollect whom they represent in our familiar orbit. Also, Song has made a nice ethical choice in coupling this Sissy character with a less stereotyped, Ska-influenced boyfriend so as not to leave us with the Sissy as the sole Queer representation within the film.) What is most striking about these discomforting interactions with men is that there is no striking. That is, no male violence upon women. There are moments where we'd almost expect violence, such as Ok-nam's shameful meeting with her husband at the police station, given the Korean film tropes that came before and after. But in most of these interactions, the men eventually offer non-patriarchal moments of concern and comfort towards the collective plight of these women, assisting them in their quest rather than restricting their movement.

Beyond the similarities with Nabi's premise, Flower Island appears to present how making unpleasant matters "disappear" is within our grasp if we stick together, that is, to paraphrase Ok-nam, 'learn from our angel friends', or in metaphorical terms different from Ok-nam's, our allies in our journey. Ok-nam's magic tricks with her daughter, Hye-na's rave-ish costumes and rituals, Yoo-jin's emotive singing, they all can demonstrate a disappearance from the pain/boredom of the everyday. Song even extends this solidarity into the audience when Ok-nam's friend hypnotizes Yoo-jin to help alleviate her grief. Song places blank screen frames intermittently within this scene while Ok-nam's friend counts Yoo-jin into and out of a trance, as if she is asking us to comply with the her instructions as well. Like the 'breathe in/breathe out' at a doctor's office that begins Apitchatpong Weerasethakul's Blissfully Yours, we are asked to meditate along with the characters of the film.

Just as the Nabi connection is not a fully applicable one, I find myself wanting to claim connections between Flower Island and Oshima Nagisa's, In The Realm of the Senses. But any connection that may exist is not one I can solidly argue and perhaps more influenced by my recently purchasing Joan Mellen's addition to the British Film Institute's series of film monographs than by what is presented in the film. These possible references just strangely sit there to make more out of them than they are. And perhaps this desire to digressively reach on my part represents how this film was reaching too far as well, resulting in my trying too hard to piece together this filmic fabric into something more than it is. Regardless of the swatches of interest I can cut out from the film, Flower Island, even after a second viewing, fails to fit as a full ensemble. I am left with interesting fragments, but I wouldn't list this film as a must-see outside of those who have an interest in investigating the origins of greater themes in Song's later works. In this way, Flower Island appears to be Song's Motel Cactus, a resting stop of interesting but unfulfilling locales on route to the more refreshing cinema that the camel(s) have found in Song's recent work... or so I've heard. (Adam Hartzell)

Comic books are more popular in Asia than in any other part of the world, and in Volcano High we get a movie that aspires to the look and feel of Asian comics. Bizarre, disjointed, and at times obnoxious, the film is nonetheless true to its word, and it delivers a distinctive visual and auditory rush.

Set during an unspecified time frame which mixes bits of the past and future, Volcano High tells the story of a high school student with intense supernatural powers. Able to lift objects and hurl them through space with his mind, he nonetheless has problems with control, which gets him expelled from eight successive high schools. When he arrives at his ninth, a place filled with other students much like him, he is desperate to avoid expulsion, but harassment from other students (and teachers) makes his internal struggle more and more difficult to bear.

Set during an unspecified time frame which mixes bits of the past and future, Volcano High tells the story of a high school student with intense supernatural powers. Able to lift objects and hurl them through space with his mind, he nonetheless has problems with control, which gets him expelled from eight successive high schools. When he arrives at his ninth, a place filled with other students much like him, he is desperate to avoid expulsion, but harassment from other students (and teachers) makes his internal struggle more and more difficult to bear.

This is the third film for director Kim Tae-kyun, whose previous works were in romantic comedy: The Adventures of Mrs. Park (1996) starring Shim Hye-jin and Shall We Kiss? (1998) starring Ahn Jae-wook and Choi Ji-woo. When casting for his new film, he decided that a new-styled genre deserves new actors, so he chose Jang Hyuk and Shin Min-ah for his leads, both of whom are making their film debut. The roles they take must have been a challenge, given the film's schizophrenic leaps between different moods, but they pull it off rather well. It's the older actors who steal the show, however, particularly the neurotic vice principal, played by Byun Hee-bong, the man who narrates the story of "Boiler Kim" in Barking Dogs Never Bite.