Park Chan-wook's World of Personal Introspection:

The Subtext of Cinematic Space in Old Boy

by Boris Trbic

Contemporary critical canon regards urban culture as a symbolically constituted text, a mosaic of models, meanings and discourses embodied in the totality and diversity of conditions, circumstances, customs, conventions and relationships which form and shape the social and cultural life of city dwellers. Charles Jencks sees the city as a problem of organised complexity, articulating urban pluralism and seeking radical eclecticism and multiple coding in its attempt to cut across the variety of styles and the diversity of tastes. Christine Boyer asserts that "[T]he actual space of the city is a layered and stratified, fragmented and disconnected archaeological site -- each spectator in the city holds onto multiple positions and views innumerable fragments that constantly come into play." Boyer suggest that, "[T]o fully appreciate or be able to read this cityscape as text, [however], spectators are required to look at the city not only in formal and functional terms, but in figural or interpretive ways as well." Allan Jacobs and Donald Appleyard delve even further, examining the narrative complexity of urban aesthetics, and point out that "[A] city should present itself as a readable story, in an engaging, and, if necessary, provocative way, for people are indifferent to the obvious overwhelmed by complexity."

Film cities, whilst fictional constructs, perpetually reaffirm the central paradigm of the contemporary critical canon; that truth, justice and reality cannot be observed in isolation from the human mind and that there is no universal interpretative ground for establishing a reliable vision of the world. The urban architecture in Park Chan-wook's films uncovers a complex web of interconnections and persistently reflects the equivocal signals that contradict, reconstruct and reformulate his cinematic settings. The filmmaker challenges, problematises and transforms his film space accumulating and accentuating diverse and often conflicting spatial elements in order to discover appropriate framework for his narratives. The cinematic space in his latest film, Old Boy, is both persuasive and elusive, generating an overall sense of instability and subverting the coherent reading of his text. It frames, contextualises and typifies one of the most persistent poetic motifs in Park Chan-wook's work - an omnipresent contrast between the relentless attempts of his heroes to identify, formulate and transform the fundamental patterns of their unsatisfactory human condition, and the painful, paralysing acknowledgement that, limited by the totality of power relations, they are not in a position to determine or understand the nature of their experiences and to control and articulate their actions. Examining the cinematic spaces of personal introspection in this meticulously structured and highly evocative cinematic text, may provide a framework for the discussion of Park Chan-wook's poetics and the way it pertains to the cultural experiences of the audience.

The Prison

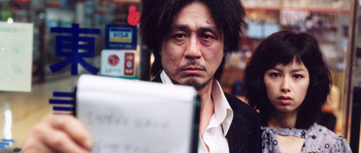

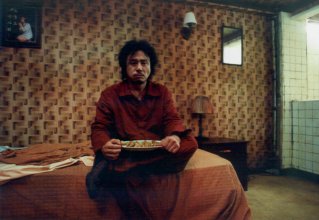

At the onset of the film, Park Chan-wook focuses on the main protagonist, a disgruntled businessman Oh Dae-su (Choi Min-shik) who is confined by a group of criminals and spends fifteen years in a private prison. The film metaphor of urban space as the place of confinement is probably as old as the cinema itself. However, in Park Chan-wook's film, the urban maze does not merely turn against the innocent citizen, as is the case in the noir series and the classic films of Welles and Hitchcock, or reflect his/her unbearable circumstances as in Fassbinder's 1970s films. The seemingly naturalist prison cell in Old Boy is removed from everyday 'reality,' and emerges as a deeply personal, individualised space. The squalid flat on the outskirts of the city reflects the state of mind of the psychotic, disturbed urban dweller, a fragment of his inexplicable ordeal. Oh Dae-su is confined to the dilapidated room with a bed, basic toilet facilities, a small, distant window, a TV set -- the only contact with the outside world -- a cuckoo watch, a desk and a lamp. In the centre of the room, we see a grotesque, demonic portrait -- a call for introspection -- that with time begins to resemble the central character. This detail seems far more disturbing than the subhuman conditions in the jail in which the inmates are held indefinitely and without justification. Heralding the disastrous quest of Oh Dae-su, Park Chan-wook infers that the brutality and hostility of the urban environment are inextricably entwined with the suffering of his hero. It is not surprising that the tales of death and misery, triggered by the trauma of unrequited love permeate the urban space in which Oh Dae-su, ironically, longs to return.

At the onset of the film, Park Chan-wook focuses on the main protagonist, a disgruntled businessman Oh Dae-su (Choi Min-shik) who is confined by a group of criminals and spends fifteen years in a private prison. The film metaphor of urban space as the place of confinement is probably as old as the cinema itself. However, in Park Chan-wook's film, the urban maze does not merely turn against the innocent citizen, as is the case in the noir series and the classic films of Welles and Hitchcock, or reflect his/her unbearable circumstances as in Fassbinder's 1970s films. The seemingly naturalist prison cell in Old Boy is removed from everyday 'reality,' and emerges as a deeply personal, individualised space. The squalid flat on the outskirts of the city reflects the state of mind of the psychotic, disturbed urban dweller, a fragment of his inexplicable ordeal. Oh Dae-su is confined to the dilapidated room with a bed, basic toilet facilities, a small, distant window, a TV set -- the only contact with the outside world -- a cuckoo watch, a desk and a lamp. In the centre of the room, we see a grotesque, demonic portrait -- a call for introspection -- that with time begins to resemble the central character. This detail seems far more disturbing than the subhuman conditions in the jail in which the inmates are held indefinitely and without justification. Heralding the disastrous quest of Oh Dae-su, Park Chan-wook infers that the brutality and hostility of the urban environment are inextricably entwined with the suffering of his hero. It is not surprising that the tales of death and misery, triggered by the trauma of unrequited love permeate the urban space in which Oh Dae-su, ironically, longs to return.

The School

The main protagonists in Old Boy are linked by a set of tragic events buried in the recollections of their high school days. Park Chan-wook uses Sangkok High School website to introduce the setting, and blends the virtual world with the blurred legacy of the past. High school reminiscences are important for Oh Dae-su and give a particular dimension to his quest. The symbolic return to school is an ultimate opportunity to learn something about oneself, and help continue his shattered existence. Yet, the melancholy and nostalgic yearning for the past are substituted by a sense of fear and apprehension, as Oh Dae-su realises that he himself was from the very beginning implicated in the object of his quest.

Cold and deserted, the seemingly naturalist setting of the school campus emerges as yet another space of personal introspection. Oh Dae-su's reminiscence is deliberately staged, stylised, and, as he traces his own footsteps, it begins to look like a re-enactment of a long forgotten crime. The classroom scene that Oh Dae-su observes through the broken window is imbued with voyeuristic overtones. The intense blues and reds permeate the traumatic experience as the musical motif links the fragments of the disconnected narrative. The couple in the science lab are seen as naive and innocent while Oh Dae-su, anguished by his unexplained suffering, for the first time emerges as an intruder, a perpetrator.

The Penthouse Apartment

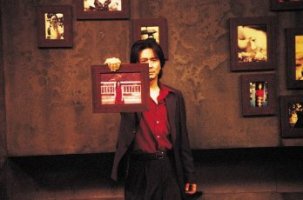

The final confrontation between Lee Woo-jin (Yu Ji-tae) and Oh Dae-su takes place in a lavish apartment, a blend between a living habitat and an office, occupying a floor in a high-rise building overlooking the city. The water features, neat and regimented seating arrangements and large glass panels, facing the central business district, imply power and control. They are juxtaposed to the intriguing, evocative and highly personal fragments of the past that surround

the two main characters. The haunting presence of framed photographs and the playing of recorded conversations suggests dark and menacing overtones in their evocations of the past. Self-absorbed and narcissistic, Pak Chan-wook's characters finally begin to recognise the pain and misery they inflicted on those they loved most. Discovering the truth behind his ordeal, Oh Dae-su attempts to redeem himself, asking for forgiveness and cutting off his tongue in agony. The subdued suffering of Yu Ji-tae emerges even more brutal and devastating. His painstakingly slow and detailed way of getting-dressed, precedes the cold, business-like confrontation with his adversary. Nevertheless, as he descends in the elevator/time capsule, reminiscing on the sombre event that changed his life, he is far from a callous master-minder who doles out punishment. Yu Ji-tae's suicide is the final act of a distraught human figure determined to end his suffering.

The final confrontation between Lee Woo-jin (Yu Ji-tae) and Oh Dae-su takes place in a lavish apartment, a blend between a living habitat and an office, occupying a floor in a high-rise building overlooking the city. The water features, neat and regimented seating arrangements and large glass panels, facing the central business district, imply power and control. They are juxtaposed to the intriguing, evocative and highly personal fragments of the past that surround

the two main characters. The haunting presence of framed photographs and the playing of recorded conversations suggests dark and menacing overtones in their evocations of the past. Self-absorbed and narcissistic, Pak Chan-wook's characters finally begin to recognise the pain and misery they inflicted on those they loved most. Discovering the truth behind his ordeal, Oh Dae-su attempts to redeem himself, asking for forgiveness and cutting off his tongue in agony. The subdued suffering of Yu Ji-tae emerges even more brutal and devastating. His painstakingly slow and detailed way of getting-dressed, precedes the cold, business-like confrontation with his adversary. Nevertheless, as he descends in the elevator/time capsule, reminiscing on the sombre event that changed his life, he is far from a callous master-minder who doles out punishment. Yu Ji-tae's suicide is the final act of a distraught human figure determined to end his suffering.

It is not surprising that, at the end of the film, Oh Dae-su's symbolic death also heralds his departure from the urban environment. Accompanied by Mido (Kang Hye-jeong), he seeks solace in the Natural world, in which snow conceals all traces of human suffering. Oh Dae-su's absent, benevolent smile invokes the proximity of the sublime surroundings. His silence echoes the unspeakable secret and hope that his pain could be assuaged by the love of his child and the transcendence and sensible simplicity of the Natural world.

Notes

1 Charles Jencks, "Death for Rebirth," in Architectural Design Profile, 88, London: Academy Editions, 1990, 7.

2 Christine Boyer, "Erected Against the City," in Center, 6. 1990, 39.

3 Christine Boyer, The City of Collective Memory. Its Historical Imagery and Architectural Entertainments. The M.I.T. Press, 1994, 19.

4 Allan Jacobs and Donald Appleyard, "Toward an Urban Design Manifesto," in Journal of the American Planning Association, 53 (1), 1987, 116.

Boris Trbic is a Melbourne writer and film critic. He has written about film in Senses of Cinema, Metro, Screen Education and other Australian and overseas publications. He has worked as a member of the Documentary Panel at the Melbourne International Film Festival (2000-2004).