1960-1969

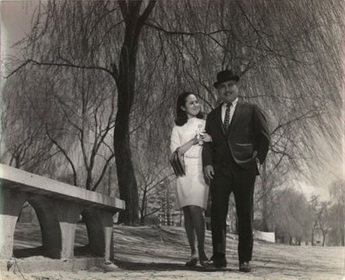

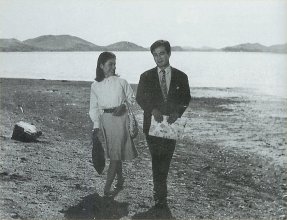

From left: "Evergreen Tree" (1961), "Aimless Bullet" (1961), "Hate But Once More" (1968), "A Devilish Homicide" (1965)

From a commercial standpoint, the 1960s stand out as an era of unprecedented strength. With television still in its infancy, moviegoing formed the primary means of entertainment for young and old alike, with the average Korean watching more than five films per year by 1966. This decade also saw the emergence of a new generation of directors, who as a group would produce some of Korea's most diverse and exciting films.

Of course, 1960s filmmaking was profoundly influenced by the political and social environment of the time. One of the defining events of this era was a series of student-led protests on April 19, 1960 which toppled the authoritarian government of Syngman Rhee. The movement's success profoundly influenced the attitudes and perceptions of younger Koreans, who had grown up during and just after the war. After April 19, for the space of a little over a year, Korean society enjoyed a much greater freedom of expression, during which films such as Kim Ki-young's The Housemaid and Yu Hyun-mok's Aimless Bullet were shot. Nonetheless in May 1961 a military coup led to the accession of dictator Park Chung-hee, who would lead the country until his assassination in 1979.

The military government introduced disruptive and authoritarian reforms which severely impacted the film industry. The first manifestation of this control came in the Motion Picture Law of 1962, which sought to introduce massive consolidation and a strong emphasis on commercial filmmaking. After passage of the law, film companies were required to own their own studios and equipment, have a minimum number of actors and directors under contract, and to produce a minimum of 15 films per year. That year, the number of film companies dwindled from 71 to 16, and soon after only 4 officially registered companies remained. Major revisions in the law would follow almost every subsequent year, making for chaos in the filmmaking community.

Directors of this era worked in an industry marked by frenzied activity. The Motion Picture Law allowed film companies to import one foreign feature for every three local movies produced, so directors were under tremendous pressure to work quickly. Movies were shot in a matter of weeks, and more popular filmmakers often turned out 6 to 8 films per year. Kim Soo-yong shot 10 features in 1967 alone, including his masterpiece Mist. Once completed, movies faced a strict government censorship board, which would often ban or delay films based on either political/social content (Yu Hyun-mok's Aimless Bullet), alleged pro-communist sympathies (Lee Man-hee's Seven Women Prisoners, for which he was briefly arrested), or sexuality (Shin Sang-ok's Eunuch).

Most directors produced a striking range of genres throughout their careers, in order to meet the voracious demands of both audiences and film companies. War films, family comedies, youth-oriented dramas, and action movies were staples of the time. Korea's first animated feature Hong Kil-dong appeared in 1967. Literary adaptations such as Mist and Guests Who Arrived by the Last Train were encouraged by the government through a point system, which awarded the producers of selected films the right to import foreign movies. Nonetheless, melodrama remained probably the most popular and influential genre of the time, often impacting works of every other genre.

Reviewed below: Romance Papa (1960) -- The Housemaid (1960) -- The Coachman (1961) -- Mother and a Guest (1961) -- My Sister is a Tomboy (1961) -- Under the Sky of Seoul (1961) -- An Upstart (1961) -- The Salaryman (1962) -- The Marines Who Never Returned (1963) -- Goryeojang (1963) -- The Reluctant Prince (1963) -- Kinship (1963) -- Barefooted Youth (1964) -- Red Muffler (1964) -- The Evil Stairs (1964) -- A Bloodthirsty Killer (1965) -- The Starting Point (1965) -- A Seaside Village (1965) -- The Student Boarder (1966) -- Space Monster, Wangmagwi (1967) -- Flame in the Valley (1967) -- Mist (1967) -- Guests Who Arrived by the Last Train (1967) -- Golden Iron Man (1968).

| Year | Local Films | Imports | Screens | Total Admissions | Ticket Price | Per Capita Adm. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1960 | 92 | 208 | 273 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 1961 | 86 | 105 | 302 | 58,608,000 | 12 won | 2.3 |

| 1962 | 113 | 79 | 344 | 59,046,000 | 18 won | 3.0 |

| 1963 | 144 | 66 | 386 | 96,059,000 | 20 won | 3.6 |

| 1964 | 147 | 51 | 477 | 104,579,000 | 23 won | 3.8 |

| 1965 | 189 | 64 | 529 | 121,697,000 | 23 won | 4.3 |

| 1966 | 136 | 85 | 534 | 156,336,000 | 31 won | 5.4 |

| 1967 | 172 | 64 | 569 | 164,077,000 | 41 won | 5.6 |

| 1968 | 212 | 63 | 578 | 171,341,000 | 51 won | 5.7 |

| 1969 | 229 | 79 | 659 | 173,043,000 | 63 won | 5.6 |

Source: The History of Korean Cinema (1988), Lee Young-il and Choi Young-chol.

Short Reviews

These are some reviews of the features released from the 1960s that have generated discussion and interest among film critics and/or the general public. They are listed in the order of their release.

Shin Sang-ok's Romance Papa begins with the artifice of introductions of each character. These introductions are a vestige of the radio play from which this story originated, but it does help this viewer from the future navigate between these characters from the past since the times required that actors and actresses of similar ages play characters much younger than themselves. Still, in some ways such introductions are unnecessary since fashion signifies their ages. Sailor outfits designate the youngest. A poodle skirt marks the college-aged woman. Once married, the oldest daughter sheds her western dress, and, at the end of each business day, her new husband his western suit, for a hanbok. There is much to be said about fashion in South Korean films. Read the discussion of hanbok fashion fusions in the 1950's by Princeton University professor Steven Chung or watch the recent documentary on fashion designer Nora Noh for examples. Romance Papa is another object of study on how necessary sartorial choices can be to character development.

Yet what follows as plot in Romance Papa is really a series of vignettes, aligning this film more with the episodic nature of modern-day TV serials than a medium demanding a status as a single unit. It is as if Romance Papa is an early precursor of the binge-watching experience enabled by the distribution system of the internet. In the single feature film of Romance Papa, we are in a sense successively viewing several episodes of the radio show in one evening. As the aforementioned Steven Chung notes in his book reconsidering our understanding of director Shin, Split Screen Korea: Shin Sang-ok and Postwar Cinema (University of Minnesota Press, 2014), "Shin consistently capitalized on the creativity of radio dramas and locked up many of the scripts during their broadcast. Other hits yielded through this practice include Confessions of a College Girl and Until the End of This Life" (p 223). A modern day equivalent to this capitalization on cross-media creativity was noted in a talk given at the Society for Cinema and Media Studies 2014 conference in Seattle by University of Ulsan professor Hwang Yun-mi. Part of the panel "Genre in Contemporary East Asian Cinema" that she chaired, Hwang's talk was entitled "Contemporary Costume Drama in South Korea: Genre and Genrification". An aspect of her talk was that the costume drama film genre feeds off the visual signifiers of the same genre of television serials in their costumes, set designs, and even culinary displays. Although in this case the rights of TV dramas are not being secured like the radio dramas of the past, the TV dramas are providing some paratextual labor in encouraging audiences to have production expectations of the film dramas from what they gather from the TV dramas. The TV costume dramas "genrify" the film costume dramas just as Shin used a radio drama to "genrify" the film Romance Papa. In this way, films like Romance Papa further demonstrate the past foundation of present South Korean media tactics. To refashion the cliché, everything new was old once.

Yet what follows as plot in Romance Papa is really a series of vignettes, aligning this film more with the episodic nature of modern-day TV serials than a medium demanding a status as a single unit. It is as if Romance Papa is an early precursor of the binge-watching experience enabled by the distribution system of the internet. In the single feature film of Romance Papa, we are in a sense successively viewing several episodes of the radio show in one evening. As the aforementioned Steven Chung notes in his book reconsidering our understanding of director Shin, Split Screen Korea: Shin Sang-ok and Postwar Cinema (University of Minnesota Press, 2014), "Shin consistently capitalized on the creativity of radio dramas and locked up many of the scripts during their broadcast. Other hits yielded through this practice include Confessions of a College Girl and Until the End of This Life" (p 223). A modern day equivalent to this capitalization on cross-media creativity was noted in a talk given at the Society for Cinema and Media Studies 2014 conference in Seattle by University of Ulsan professor Hwang Yun-mi. Part of the panel "Genre in Contemporary East Asian Cinema" that she chaired, Hwang's talk was entitled "Contemporary Costume Drama in South Korea: Genre and Genrification". An aspect of her talk was that the costume drama film genre feeds off the visual signifiers of the same genre of television serials in their costumes, set designs, and even culinary displays. Although in this case the rights of TV dramas are not being secured like the radio dramas of the past, the TV dramas are providing some paratextual labor in encouraging audiences to have production expectations of the film dramas from what they gather from the TV dramas. The TV costume dramas "genrify" the film costume dramas just as Shin used a radio drama to "genrify" the film Romance Papa. In this way, films like Romance Papa further demonstrate the past foundation of present South Korean media tactics. To refashion the cliché, everything new was old once.

The theme that runs through the synced vignettes is of the father who is a hopeless romantic, a sentimental softie who is the kind of father who wants to frame his youngest daughter's first love letter. He is so concerned about his fellow man, instead of pummeling a burglar, he wants to provide alms of seaweed for the thief who just tried to pillage his home. The only time he doesn't romanticize a daily experience is when his oldest daughter is romantically involved with a young man. Our papa has contempt for his future son-in-law's profession, meteorology. Like other sciences, meteorology is based on predicting the probability of events, which means there is always a chance of events diverging on rare occasions from the trend, but the statistical anomaly doesn't necessarily disprove the theory. Our papa, however, hyper-focuses on the predictions that are 'wrong' without seeing the wider data-compiling that leads the direction of the predictions. It appears this papa could be a precursor of climate change deniers. Except this papa is adorable rather than dangerous.

Romance Papa launched Shin Sang-ok's Shin Films production outfit and "fixed the studio's reputation for high quality filmmaking with mass appeal" (Chung, p 92). The film's popularity is partly due to the casting of Kim Seung-ho in the role of the benevolent patriarch. Kim's star status trailed him from film to film as the type of father everyone could love. He could occasionally embarrass his daughters, such as when he encourages his college-aged daughter to wear his pants for a hiking trip with her friends, or he could be gullible and believe the deliberate 'mom-said' lies his three youngest children spread at his expense, but he isn't a failure in any way, at least not in this film. He is a simple spirit that hopes for the best in everyone in every circumstance, even when there is little evidence for such hope. This papa will give credence to the the statistical improbabilities in life if that lesser is on the side of the least of us. (Adam Hartzell)

Romance Papa ("Romaenseu Bbabba"). Directed by Shin Sang-ok. Original radio play by Kim Hee-chang. Adapted by Kim Hee-chang. Starring Kim Seung-ho (Romance Papa), Joo Jeung-nyeo (Mother), Choi Eun-hee (Eum-jeon), Kim Jin-gyu (Jeon Woo-taek), Nam Kung-won (Eo-jin), Do Geum-bong (Gob-dan), Shin Sung-il (Ba-reun), Eom Aeng-ran (Ebbun). Cinematography by Jeong Hae-jun. Produced by Shin Films. 131 min, 35mm, b&w. Released on January 28, 1960. Total admissions: 100,000. Winner of Best Actor (Kim Seung-ho) at 7th Asian Film Festival.

A consensus pick as one of the top three Korean films of all time, Kim Ki-young's masterpiece The Housemaid occupies a place all its own within Golden Age Korean cinema. A domestic thriller that builds in intensity right up until its startling resolution, the film doubles as a manic tour-de-force and a cutting satire of the aspirations and values of modern society.

Based on a contemporary news story, the film focuses on a traditional four-member family which has just moved into a two-story home. The husband Dong-shik teaches music to women factory workers, while his wife spends her days at home at the sewing machine, trying to earn enough money to cover the family bills. One day she breaks down from overwork, and Dong-shik asks one of his students to find him a housemaid. However, the maid they hire acts in strange and unpredictable ways, spying on Dong-shik and catching rats with her bare hands. Soon an incident occurs which motivates her to plot a dreadful revenge, and the Confucian order of the household comes crashing down at the hands of the surreptitious housemaid.

Based on a contemporary news story, the film focuses on a traditional four-member family which has just moved into a two-story home. The husband Dong-shik teaches music to women factory workers, while his wife spends her days at home at the sewing machine, trying to earn enough money to cover the family bills. One day she breaks down from overwork, and Dong-shik asks one of his students to find him a housemaid. However, the maid they hire acts in strange and unpredictable ways, spying on Dong-shik and catching rats with her bare hands. Soon an incident occurs which motivates her to plot a dreadful revenge, and the Confucian order of the household comes crashing down at the hands of the surreptitious housemaid.

Asian cinema, and melodrama in particular, tends to portray the family as the most basic building block of society. Kim's somewhat twisted cinematic vision focuses on how the supposedly stable family unit comes apart under pressure. The two-story home in which Kim sets his film acts as a symbol for Korea's modernizing middle class, yet behind the placid surface we see darker, more primitive elements penetrating into the family's space: construction workers intruding on their daily lives, rats running amok, and the housemaid herself, wreaking havoc with envy and sexual forthrightness.

With inspired editing and a restless camera (not to mention that famous bottle of rat poison), Kim gradually heightens the sense of tension and claustrophobia, creating scenes of startling intensity. The performance he draws out of young actress Lee Eun-shim as the housemaid (on the left in the photo) is unlike anything else shot in Korea in that decade, or indeed ever since. Sadly, her brilliant acting may have ended her career -- it's said that viewers' reactions to her were so strong (audiences reportedly screamed "Kill the bitch!" during screenings) that producers were unwilling to cast her in subsequent films. As for the rest of the cast, Kim Jin-gyu brings a slightly aristocratic air to the role of Dong-shik, while Joo Jeung-nyeo plays the wife with a bland but stubborn determination to preserve appearances at all cost. The children excel in their roles too, including future star Ahn Sung-ki as the young son.

Though it debuted in 1960 as a box-office hit, The Housemaid was never given proper recognition until a retrospective of Kim Ki-young's work in 1997 at the Pusan International Film Festival. Since then, the film has gradually made its way to retrospective screenings around the world, drawing forth surprised and passionate responses from audiences wherever it goes. One hopes that with time, it will escape from the still overlooked confines of 1960s Korean cinema to become recognized as a world classic. (Darcy Paquet)

The Housemaid ("Hanyeo"). Written and directed by Kim Ki-young. Starring Lee Eun-shim, Kim Jin-gyu, Joo Jeung-nyeo, Eom Aeng-ran, Ko Sun-ae, Kang Seok-jae, Ahn Sung-ki. Cinematography by Kim Deok-jin. Produced by Korean Literature Films, Ltd. 90 min, 35mm, b&w. Released on November 3, 1960.

A single father with two sons and two daughters makes a living by operating a horse-drawn cart. However, in a city that is modernizing after the destruction of the Korean War, automobiles are making such carts obsolete, and he struggles to make ends meet.

The family's younger generation is also experiencing difficulties. The eldest son hopes to pass the bar exam to become a lawyer, but he has flunked twice already and is feeling pessimistic about his third try. The eldest daughter, who is mute, is married to an abusive husband. The younger daughter tries to move up in life by posing as a rich university student, while the youngest son has a penchant for petty theft.

The family's younger generation is also experiencing difficulties. The eldest son hopes to pass the bar exam to become a lawyer, but he has flunked twice already and is feeling pessimistic about his third try. The eldest daughter, who is mute, is married to an abusive husband. The younger daughter tries to move up in life by posing as a rich university student, while the youngest son has a penchant for petty theft.

At its heart, Kang Dae-jin's The Coachman ("Mabu") is a drama told with warmth and sympathy about a family trying to lift its way out of poverty and into the middle class. The challenges they face would have been familiar to many of its viewers in 1961, from the cruel and dismissive attitude of the upper classes to the pressure to pay back debts. The character of the father, played by the iconic Kim Seung-ho, also represents the situation faced by many older residents of the time, in not being able to cope with the quickly changing face of Korean society. Tellingly (and in patriarchal fashion), all hopes for the family's future are placed on the eldest son.

Perhaps the film's biggest strength is to highlight the frustration of having motivation and hard work matter much less than connections and money. The film walks a fine line between optimism and pessimism, but in its darker moments it offers a harsh critique of the economic foundations of society. Hope comes in the form of human generosity, whether from the understanding son of the family's creditor or the middle-aged housemaid who becomes romantically involved with the father. (A date that the older couple takes to a movie theater to see Chunhyang-jeon is one of the film's most fondly-remembered scenes)

The Coachman was the first Korean film to win a major overseas award, taking home the Silver Bear (Special Jury Prize) from the 1961 Berlin International Film Festival. It has since become recognized as one of the classics of Golden Age Korean cinema. Although somewhat overshadowed by the achievements of its contemporaries The Housemaid (1960) and Aimless Bullet (1961), The Coachman remains a crowd-pleaser and a touching portrait of a society in transition. (Darcy Paquet)

The Coachman ("Mabu"). Directed by Kang Dae-jin. Screenplay by Im Hui-jae. Starring Kim Seung-ho, Shin Young-gyun, Hwang Jeong-soon, Jo Mi-ryeong, Hwang Hae, Eom Aeng-ran, Kim Hee-gap, Joo Seon-tae, Jang Hyeok. Cinematography by Lee Moon-baek. Produced by Hwaseong Film Co. 95 min, 35mm, b&w. Rating received on February 15, 1961.

Based on the novel by Joo Yo-sup representing colonial times, Shin Sang-ok's Mother and a Guest is another film from the 1960s that considers the shifting personal ethics/morals as South Korea rapidly modernized. What interests me about this film is how those shifting morals are presented differently by two characters in the context of the class position they hold in society, the higher class mother (played by Choi Eun-hee, Shin's wife and regular muse) and her lower class maid (Do Kum-bong, Romance Papa, Evergreen Tree). They are both young widows and the moral demands of the past required them to re-chaste and not acquire a new partner. Yet, although the film was based during colonial times, the film was produced during a limnal space in time in South Korea's history where sexual ethics were changing, where female agency was acquiring greater opportunity. Yet the higher class mother still can't move, stuck within the constraints of her home, whereas the lower class maid finds some space outside the house to move. Each woman's station in society foreshadows their limitations and their freedoms. I wonder if many watched this melodrama and felt sympathy for the mother, felt righteousness in the 'need' to fire the maid after she crossed an ethical line of the time. But I also wonder if there were just as likely some audience members who saw how society imposed this suffering on both women by limiting their agency in class-specific ways, having sympathy for both the woman thrown out for her love and the woman who throws out the possibility of love.

Mother and a Guest is partially told to us through the unreliable interpretations of the mother's young daughter (Jeon Young-seon, The Marines Who Never Returned, The Ball Shot by a Dwarf). She will go back and forth between her mother and the artist houseguest (Kim Jin-gyu, The Housemaid, Aimless Bullet) with information we know is slightly incorrect. This miscommunication is partly due to her innocence in the ways of love and social propriety, but it is also because indirect communication often results in miscommunication. The mother and the artist houseguest are presented as perfect for each other except the mother is still tied down by the social norms that demand widows consider no future suitors. She is bound to her late husband and her living mother-in-law. The houseguest knows this. The audience knows this. But in the eyes of a child, and the eyes of many watching this from the vantage point of the 21st century, their unwillingness to consummate what is obviously sincerely felt doesn't make sense. As a result, out of the mouths of babes comes another love that dare not speak its name. The child unwittingly announces that the morals are changing, hoping that the houseguest can become a housemember, consummating the desire brewing between the two suffering souls.

Mother and a Guest is partially told to us through the unreliable interpretations of the mother's young daughter (Jeon Young-seon, The Marines Who Never Returned, The Ball Shot by a Dwarf). She will go back and forth between her mother and the artist houseguest (Kim Jin-gyu, The Housemaid, Aimless Bullet) with information we know is slightly incorrect. This miscommunication is partly due to her innocence in the ways of love and social propriety, but it is also because indirect communication often results in miscommunication. The mother and the artist houseguest are presented as perfect for each other except the mother is still tied down by the social norms that demand widows consider no future suitors. She is bound to her late husband and her living mother-in-law. The houseguest knows this. The audience knows this. But in the eyes of a child, and the eyes of many watching this from the vantage point of the 21st century, their unwillingness to consummate what is obviously sincerely felt doesn't make sense. As a result, out of the mouths of babes comes another love that dare not speak its name. The child unwittingly announces that the morals are changing, hoping that the houseguest can become a housemember, consummating the desire brewing between the two suffering souls.

Forbidden desire biding time for society to allow for eventual release provides perfect tension for melodramas. Steven Chung notes in his excellent overview of the career of Shin Sang-ok, Split Screen Korea: Shin Sang-ok and Postwar Cinema (University of Minnesota Press, 2014), how "this yeui vs. chong (duty vs. feeling) conflict is played out" (p 73) in Mother and a Guest at an interpersonal level on the body of the mother. (And by extension, this conflict was imposed on the body of actress Choi Eun-hee in that this became one of her iconic roles.) As for the social level of the yeui vs. chong conflict, Chung sees a greater emphasis on that level in Shin's film Tongsimch'o (1959).

Yet, as stated in the paragraph above, I see Mother and a Guest also working at the social level. (That is, if I am correctly reading "social level" as synonymous with "societal level".) The presence of the parallel digression from social expectations in the widowed maid and her egg-seller suitor allows for a release of tension from the unfulfilled desire between the mother and the houseguest. The maid's nausea signifies her pregnancy and alludes to the consummation of the widowed maid and egg-seller's desire. As a result, the maid's vomiting releases the yeui vs. chong tension building up inside of these bodies onscreen and within the bodies of the audience members watching the screen. The maid/egg-seller romance is the perfect subplot to consider if not critique the morals of the time. An ironic purity is still required of the mother over the maid. But it is this counter-resolution of plots that results in a satisfying viewer experience regardless of the moral strictures by which one is bound.

Chung notes how Shin deflected any characterizations that his films were feminist. As Chung summarizes, "In nearly all of his work, women must either repress their need for emotional fulfillment or sexual pleasure or are punished for their transgressions of social restriction" (p 113). Yet, although the maid is 'punished' in that she loses her job, she expresses fulfillment later in the film. Plus, the mother-in-law does hint at the possibility of change at the higher level of society too. Shin's film may have succeeded with audiences not solely because it reinforced society's patriarchal demands on women, but because the film also provided temporary release for desires that had a much harder time being fully realized outside the theatre. Mother and a Guest might have gently nudged greater possibilities for female agency on screen that later found expression on the streets (and in the bedsheets) of South Korea as she rushed along towards modernization. (Adam Hartzell)

Mother and a Guest ("Sarangbang sonnimgwa eo-meoni"). Directed by Shin Sang-ok. Original short story by Joo Yo-sup. Adapted by Lim Hee-jae. Starring Choi Eun-hee (Mother), Kim Jin-gyu (Guest), Jeon Young-seon (Ok-hee), Han Eun-jin (Grandmother), Do Geum-bong (Housemaid), Kim Hee-gap (Egg seller), Shin Young-gyun (Uncle), Heo Jang-gang (Fortune -teller). Cinematography by Choi Soo-young. Produced by Shin Films. 102 min, 35mm, b&w. Rating received on August 26, 1961. Total admissions: 150,000. Winner of Best Director, Best Screenplay, Special Mention(Jeon Young-seon) at 1st Grand Bell Awards, Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actress(Choi Eun-hee) at 5th Buil Film Awards.

In his chapter in the larger volume The Korean Popular Culture Reader (edited by Kyung Hyun Kim & Youngmin Choe, Duke University Press, 2014), Steven Chung discusses the many "spaces, media, and instruments that provoked or accommodated socially significant visual phenomena in the 1950s" (p 106) in South Korea. One of these "sites of spectacle and visual consumption" was the public park that enabled "the public pastime of people watching". And it is in a public park at the beginning of Han Hyeong-mo's My Sister is a Tomboy, where two young men up to no good stumble upon Ahn Sun-ae (Moon Jung-sook) and her younger sister Ahn Seon-hui (Uhm Aeng-ran) taking photos of themselves. The young men eventually photobomb a snapshot after which Sun-ae destroys the film in disgust, angry at the sexist entitlement shown by these young men. After a drastic shift in demeanor, the four stroll to a secluded area in the park where Sun-ae proceeds to toss the men around like rag dolls thanks to the impressive judo skills she learned at her father's judo school.

Chung notes how the most dominant medium and site for people-watching was cinema, so Han's scene hear deliciously layers the people-watching of cinema upon a scene of people watching in the park. And although we have a moment of gender rebellion with the judo tosses, the scene also sets up who will really be controlling the framing in this picture. Before the young men photobomb the sisters, Sun-ae makes a mistake with the camera and the men ridicule her for this. Then, when Sun-ae picks up the photos from the developer, the end results further reinforce she is not a good photographer. Although she blames the developer at the photo studio, Na Ju-o (Kim Jin-gyu - Aimless Bullet & The Housemaid) and this enables her to meet-rude her eventual suitor, all of this is foreshadowing that Sun-ae's attempts to recreate her world to fit a frame outside of the male gaze will be disrupted by the demands of those who still control the camera.

Chung notes how the most dominant medium and site for people-watching was cinema, so Han's scene hear deliciously layers the people-watching of cinema upon a scene of people watching in the park. And although we have a moment of gender rebellion with the judo tosses, the scene also sets up who will really be controlling the framing in this picture. Before the young men photobomb the sisters, Sun-ae makes a mistake with the camera and the men ridicule her for this. Then, when Sun-ae picks up the photos from the developer, the end results further reinforce she is not a good photographer. Although she blames the developer at the photo studio, Na Ju-o (Kim Jin-gyu - Aimless Bullet & The Housemaid) and this enables her to meet-rude her eventual suitor, all of this is foreshadowing that Sun-ae's attempts to recreate her world to fit a frame outside of the male gaze will be disrupted by the demands of those who still control the camera.

The basic plot of Tomboy is how to marry off the gender-nonconforming oldest sister Sun-ae since cultural expectations at the time require the eldest be married first. And since younger sister Seon-hui already has a prospective partner, artist boyfriend Noh Si-o (Lee Dae-yup), they decide to engage in some matchmaking. The photo developer from before, Ju-o, is friends with Si-o and Si-o knows Ju-o likes tomboys. The father of the two sisters is happy to have someone interested in his oldest daughter, so it is Sun-ae who persists as the main obstacle. Seeing her continued resistence, the father begins to suspect his efforts to teach his oldest daughter self-defense through judo has backfired and made her unwilling to marry.

The actor playing Ahn Dal-su, the father of the sisters, is everyone's favorite patriarch from the Golden Age of South Korean Cinema, Kim Seung-ho. Kelly Joeng so perfectly summarizes Kim's appeal in her chapter of the aforementioned volume that I will quote her at length where she writes how Kim . . .

... was popular precisely because he presented the nostalgic father - rather than the real father of the present, of the extradiegetic world. Through his roles he came to represent both the ideal and typical fathers, successfully creating an image of "the father" by repeatedly playing an archetypical role even while imbuing it with the reality of the quotidian details. Such a character appealed to audiences' sense of longing for the unspecified, pre-lapsarian golden past and a strong patriarch. This is a father-as-the-law figure, who is both capable and incorruptible (p 132, italics in the original).

As Richard Dyer's pioneering work on star studies has demonstrated, stars are able to contain contradictions, and Kim's ability to hold on to contradictions of "both the ideal and typical fathers" is on full display in My Sister is a Tomboy. Early on, Kim scolds his young son Ahn Yong-sik (a very young Ahn Sung-ki - Chilsu and Mansu & Nowhere To Hide) for mistreating an animal. Immediately afterwards, the camera shows the father plucking a dead chicken. (The camera focusing on the chicken during the dialogue is all we need to witness this hypocrisy, but director Han feels this contradiction must be underscored by dialogue so no one misses it, ruining the power of the shot to this modern viewer.) It is here that the father laughs to acknowledge his hypocrisy, foreshadowing the scene where he punishes Sun-ae with judo throw after throw for her refusal to conform to gender norms when previously he'd encouraged her to learn judo. Ok, well, he says it is to punish her for using the judo skills aggressively rather than solely for self-defense as he intended. But he is contradicting himself in that very scene because he is using the same judo skills to punish her, not to protect himself. This is disturbing for the feminist-aspiring viewer, especially since Han ties the violence to patriotic correctness by centering Taegukgi, the South Korean flag, in this scene.

I can only imagine what it would be like for the gender nonconforming Koreans in the audience in 1961. Were they able to find some catharsis in Sun-ae's earlier throws of the men and excise from their memory the father's punishment? Could Sun-ae's pre-marriage scenes enable hope and relief for audience members who might be the equivalent of today's young folk who relish in KPop star Amber's confident female masculinity? I would love for someone to research this, if primary documents exist. As Chung notes, critics in the 1990s brought feminist film theory and sociology to the films of the Golden Age.

Rather than engaging strictly with the films' expressions of cultural identity, they began looking more closely at the politics of spectatorship and reception as well as the social life of melodrama as a cinematic form. While skeptical about the patriarchal discourses in films such as Madame Freedom and Hellflower, they saw those films as potentially radical and empowering events for the lower class, middle-aged women who made up the majority of audiences (p 120).

There were likely woman rooting for Sun-ae to be 'taught a lesson' by the patriarchal stand-in that was Kim's persona, but his contradictions of loving father and stern disciplinarian here perhaps also enabled some woman who silently maneuvered around the patriarchy to find virtual visceral joy when Sun-ae was doing the tossing, even if they knew they couldn't vocalize their feelings in public. And the film closes with an interesting nuanced difference of the knight in a shining armor cliche. Most critics would never call Han a feminist filmmaker, (and I am among those critics), but his films are so ripe for feminist interrogation. It's not hate-watching, but more curiosity in exploring the contradictions in patriarchal patriotism.

There were likely woman rooting for Sun-ae to be 'taught a lesson' by the patriarchal stand-in that was Kim's persona, but his contradictions of loving father and stern disciplinarian here perhaps also enabled some woman who silently maneuvered around the patriarchy to find virtual visceral joy when Sun-ae was doing the tossing, even if they knew they couldn't vocalize their feelings in public. And the film closes with an interesting nuanced difference of the knight in a shining armor cliche. Most critics would never call Han a feminist filmmaker, (and I am among those critics), but his films are so ripe for feminist interrogation. It's not hate-watching, but more curiosity in exploring the contradictions in patriarchal patriotism.

Chung's contribution in his chapter, along with his excellent book Split Screen Korea: Shin Sang-ok and Postwar Cinema (University of Minnesota Press, 2014), emphasizes the importance of fashion in South Korean films of this time. In the case of Sun-ae here, she wears the 1950s style dresses when outside but pants inside the house. She'd likely prefer to wear the pants outside too, but she's aware of how much she can push against the demands of the time. In addition, when the sisters are finally married off, Seon-hui immediately starts wearing a hanbok, but Sun-ae delays acquiring this sartorial gesture, demonstrating she is still resistant to subscribing to the gender roles required in a marriage at this time.

Besides the use of fashion, Han's films are fodder for further investigation of early sports cinema in South Korea. Along with the judo on display here, Han's The Female Boss has significant scenes of a basketball game. In addition, I am not alone in considering dance a 'sport' since physical excellence is required, so we can include the iconic night-club scene in Han's masterpiece Madame Freedom as well. Again, this is the spectacle of cinema focusing on another spectacular form of entertainment. And another reason why Han's films deserve greater global attention, as long as we bring our feminist and sociological perspectives to curtail the harmful demands that only certain gender expressions are permissible and they must be violently suppressed when expressed 'too far'. (Adam Hartzell)

My Sister is a Tomboy ("Eonni-neun malgwal-ryang-i"). Directed by Han Hyung-mo. Screenplay by Gwak Il-ro, Park Seong-ho, Yoo Il-su. Starring Moon Jung-sook, Kim Jin-gyu, Eom Aeng-ran, Lee Dae-yup, Kim Seung-ho, Choi Nam-hyun, , Ahn Sung-ki. Cinematography by Lee Seong-hwi. Produced by Hab Hyung-mo Productions. 98 min, 35mm, b&w. Total admissions: 50,000.

The opening of Under the Sky of Seoul consists of a series of birds-eye shots of various neighborhoods in Seoul. Set to jaunty music, and photographed with visual flair, it serves to locate the story in a real, contemporary space, and to plant the idea of "community" firmly in the viewer's head. The year 1961 was a suitable time to be thinking of urban communities. Seoul was eight years into its post-war reconstruction effort, and many of the city's residents had recently moved in from the countryside. The old neighborhoods had changed, and South Korea was modernizing.

Adapted for the screen from a novel by Jo Heun-pa, Under the Sky of Seoul centers around the character of Kim Hak-kyu, a doctor of Oriental medicine played by the era's iconic patriarch, actor Kim Seung-ho. A crabby, traditional sort of man, Kim is mortified to learn that his two grown children have fallen in love with the wrong sort of people. His daughter (Choi Eun-hee), a hairdresser who was widowed during the war, has eyes for the smart, well-educated doctor (Kim Jin-gyu) who runs a Western-style OB-GYN clinic across the street. Kim Hak-kyu fumes that the match is beneath the dignity of his illustrious family, but beneath his tirade lurks a business rivalry and sense of threat. Meanwhile, the son (Shin Young-gyun) has been secretly dating Jeom-rye (Do Geum-bong), the daughter of a local tavern owner. Their secret is about to break into the open, however: Jeom-rye is pregnant.

Adapted for the screen from a novel by Jo Heun-pa, Under the Sky of Seoul centers around the character of Kim Hak-kyu, a doctor of Oriental medicine played by the era's iconic patriarch, actor Kim Seung-ho. A crabby, traditional sort of man, Kim is mortified to learn that his two grown children have fallen in love with the wrong sort of people. His daughter (Choi Eun-hee), a hairdresser who was widowed during the war, has eyes for the smart, well-educated doctor (Kim Jin-gyu) who runs a Western-style OB-GYN clinic across the street. Kim Hak-kyu fumes that the match is beneath the dignity of his illustrious family, but beneath his tirade lurks a business rivalry and sense of threat. Meanwhile, the son (Shin Young-gyun) has been secretly dating Jeom-rye (Do Geum-bong), the daughter of a local tavern owner. Their secret is about to break into the open, however: Jeom-rye is pregnant.

These and other conflicts drive the plot forward, sticking to a ratio of roughly three parts humor to two parts sentiment. The story actually encompasses quite a few more characters, and I won't take the time to introduce them all here. But the film's ambition to take in the whole neighborhood gives it somewhat the feel of an anthropological study. The large number of characters also provided an excuse for major studio Shin Film to cast just about every significant star of its day. About halfway through the film, I thought to myself, "My god, this movie has everyone except Shin Sung-il." And sure enough, a few scenes later the man appears, playing an Air Force captain.

Director Lee Hyeong-pyo shot more than 80 films in a career that lasted 25 years, but he remains best known for this, his feature debut. He began his career working for the United States Information Service doing subtitle translations, and was also an interpreter and assistant director for the Hollywood 3-D war film Cease Fire! shot by Paramount on location during the closing days of the Korean War. His work as a cinematographer under Shin Sang-ok for Dongsimcho (1957) and Seong Chunhyang (1961) paved the way for his debut at Shin Film. Upon its release, Under the Sky of Seoul attracted reams of critical praise, and was invited to both the 9th Asia Pacific Film Festival and the 3rd Frankfurt Film Festival.

Handsomely shot, Under the Sky of Seoul has something of the charm of contemporary Korean TV dramas. In fact, it's generally the case that the modern-day descendants of the 1960s Korean family comedy are to be found on television, not in the theater. Scholars have noted that this film's basic setup involving conflict between a "traditional Korean home" and a "Western home" has been re-imagined numerous times over the years on television, most notably in What Is Love?, the 1990s drama that arguably launched the Korean Wave in China.

From a contemporary perspective, one of the most eye-catching aspects of this film is its portrayal of the younger generation as compared to the old. Although the weaknesses and idiosyncrasies of the older generation are treated with warmth and humor, they stand in stark contrast to the resourcefulness and confidence of the younger characters. The film never lets you doubt for a moment that it is the youth to whom Korea should entrust its future. It's a touchingly optimistic perspective, released one year after student-led demonstrations brought down the autocratic government of Syngman Rhee. Alas, it would not take long for the elders to reassert their authority. (Darcy Paquet)

Under the Sky of Seoul ("Seoul-ui jibung-mit"). Directed by Lee Hyeong-pyo. Screenplay by Kim Ji-heon. Starring Kim Seung-ho (Kim Hak-kyu), Huh Jang-gang (Park Joo-sa), Kim Hee-gab (Noh Mong-hyun), Choi Eun-hee (Kim Hyun-ok), Kim Jin-kyu (Choi Doo-yeol), Shin Yeong-kyun (Kim Hyun-gu), Do Geum-bong (Jeom-rae), Han Eun-jin (Kim Hak-kyu's wife), Hwang Jeong-soon (Jeom-rye's mother), Koo Bong-seo (Chang-ho), Shin Sung-il (Yeong-gil). Cinematography by Choi Soo-young. Produced by Shin Film. 123 min, 35mm, b&w.

Director Kim Soo-yong is best recognized now for his adaptations of important Korean literary works, such as Mist (1967) and Seaside Village (1965), or for his later, stranger modernist films Night Voyage (1977) and Splendid Outing (1977). But at the very start of his long career, he was known in the film industry as a "comedy specialist." It may not have been his genre of choice, but reviews from the time suggest that he excelled at it. So it's a shame that prints no longer exist for all five of the comedies he made between 1958-1960.

An Upstart was shot by major studio Shin Film in 1961 and released in July, just two months after the military coup that brought Park Chung-hee to power. At first glance it looks to be little more than a star vehicle for comedian Koo Bong-seo, whose name is even included in the Korean title ("Koo Bong-seo's Striking It Rich"). But it is significantly more than that. Directed with obvious care and creativity, this is an entertaining film that stands out for its playful manipulations of sound and image, the strong acting of the cast as a whole, and especially the nuanced performance of its star.

An Upstart was shot by major studio Shin Film in 1961 and released in July, just two months after the military coup that brought Park Chung-hee to power. At first glance it looks to be little more than a star vehicle for comedian Koo Bong-seo, whose name is even included in the Korean title ("Koo Bong-seo's Striking It Rich"). But it is significantly more than that. Directed with obvious care and creativity, this is an entertaining film that stands out for its playful manipulations of sound and image, the strong acting of the cast as a whole, and especially the nuanced performance of its star.

Maeng Soon-jin (Koo) is an ordinary salaryman, not particularly special in any way, although the landlord's daughter (Do) and his boss's daughter (Jeon) each seem to find him charming. He has money troubles -- his meager salary is already spent by the time he receives it -- but his resigned approach to life's pitfalls helps to see him through. One day, out of the blue, he is visited by an American woman (who, inexplicably, speaks passable Korean). She tells him she is the widow of a U.S. veteran whose life Maeng once saved during the Korean War. Recently deceased, the man has included Maeng in his will. The payment due to him is $20 million.

$20 million is a decent chunk of cash even by today's inflated standards; in poverty-stricken postwar Korea, it was an absurdly large figure. News of the inheritance propels Maeng onto the front pages and he becomes an instant celebrity. At once, people who formerly treated him with disdain are groveling at his feet. But Maeng is ill-prepared to deal with the ramifications of his sudden riches.

As a light satire, An Upstart is not so much laugh-out-loud funny as it is consistently inventive, engaging, and amusing. The look on Maeng's face as he tries to make sense of his situation is one of the film's enduring images. Pulled and pushed in every direction, his expression remains much the same: all he wants is to find a bit of stability in this crazy world. And ultimately, though the film never gives off airs of trying to lecture its viewers, it forces you to consider some of the absurdities inherent in vast wealth. Although it certainly doesn't look like a film that is critiquing the capitalist system, in the end, it sort of is.

Koo, a former stage actor, very quickly rose to stardom after making his film debut in 1957. People say that audiences would start laughing as soon as his face appeared onscreen, before he even cracked a joke. But even though he was best known for an exaggerated, slapstick mode of humor, he was capable of turning in performances of surprising nuance and depth. This film provides a glimpse of both sides: the broad humor that made him so popular, and the finely tuned acting for which he never received proper recognition. Although at times he seems to be channeling Chaplin (his acknowledged role model), he maintains perfect comic poise while imparting a real humanity to his character. As much as the film benefits from Kim Soo-yong's inspired direction and the great performances of the other actors, in the end Koo well deserves his place in the film's title. (Darcy Paquet)

An Upstart ("Gu Bongseo-ui byeorak buja"). Directed by Kim Soo-yong. Screenplay by Park Yong-min. Starring Koo Bong-seo, Do Geum-bong, Yang Seok-cheon, Lee Jong-cheol, Jeon Gye-hyun, Joo Seon-tae. Cinematography by Choi Gyeong-ok. Produced by Shin Film. 114 min, 35mm, b&w.

Early on in Lee Bong-rae's The Salaryman, our patriarch (Kim Seung-ho) is placed in an ethical dilemma – enable the boss in his plan to embezzle money from the company, or get fired. Within these limited choices imposed by those in power over his well-being, he chooses the latter. Having given his last month's wages to a writer friend extremely down on his luck, our patriarch's economic position becomes dire in its own way, with bill collectors as reliable and punctual as he is coming by his house. Following his firing, he soon finds his options for work are limited due to age discrimination in the job market. Eventually he finds hope in a position that explicitly states age is not a negative mark. All he has to do is excel at the exam, which he's convinced is sure to be a shoe-in considering his experience. Unfortunately, he soon discovers the exam for the position is merely a formality. The promising position has already been promised to his daughter, (who had to quit school to help the family), by the man she's courting at the same firm.

The Salaryman is a variation on the oft-told morality tale of why bad things happen to good people. Our patriarch is a sensible, upstanding member of the community. He teaches his children about ethical matters as minor as punctuality and as major as democracy. (Although when his father stops his son from urinating in the street, our patriarch finds his words used against him. "It's a free country" the small, smart-ass says.) Our patriarch is a man beloved in his neighborhood. The neighborhood boys form a fan club of sorts, parading around and praising his ethics after he sees to it that a missing ball is returned to the rightful owner. Even though he doesn't make the unethical choice at the beginning, he does stray a few times, lying about dying to avoid paying a bill and asking his daughter to help him cheat on the job exam. Still, overall we have a lovable father for whom you feel pity that he's in the precarious position he is after making the just choice. We feel for the man's troubles when he proclaims "I'm utterly useless" late in the film. We all know how this will end. Just as a film in the United States under the Hays Code promoted the punishment of the 'uppity' woman or the Lesbian or Gay man, the South Korean film of this time expects a sentimental resolution that reinforces 'traditional' family roles. Acknowledging that, I was able to hold back my circa-cynic quite well. I allowed the film to be a product of its time.

The Salaryman is a variation on the oft-told morality tale of why bad things happen to good people. Our patriarch is a sensible, upstanding member of the community. He teaches his children about ethical matters as minor as punctuality and as major as democracy. (Although when his father stops his son from urinating in the street, our patriarch finds his words used against him. "It's a free country" the small, smart-ass says.) Our patriarch is a man beloved in his neighborhood. The neighborhood boys form a fan club of sorts, parading around and praising his ethics after he sees to it that a missing ball is returned to the rightful owner. Even though he doesn't make the unethical choice at the beginning, he does stray a few times, lying about dying to avoid paying a bill and asking his daughter to help him cheat on the job exam. Still, overall we have a lovable father for whom you feel pity that he's in the precarious position he is after making the just choice. We feel for the man's troubles when he proclaims "I'm utterly useless" late in the film. We all know how this will end. Just as a film in the United States under the Hays Code promoted the punishment of the 'uppity' woman or the Lesbian or Gay man, the South Korean film of this time expects a sentimental resolution that reinforces 'traditional' family roles. Acknowledging that, I was able to hold back my circa-cynic quite well. I allowed the film to be a product of its time.

And The Salaryman further underscores how enjoyable the films of this time, the 1960's, are. Even in spite of the ten minutes or so of muted visuals in the only extant print, I was engaged throughout and found the relationship of this father with the rest of his family endearing in its construction. There is even a lovely flicker of a feminist fissure in the text. The father laments how his daughter "took" his job, but we all saw him in that classroom cheating, whispering assistance with the answers. So although the 1960's needed the patriarch re-pedestaled as pillar of the family, The Salaryman isn't as heavy-handed about it as other films I've seen. Plus, there's enough rumbling from South Korea's rapid modernization requiring re-thinking of 'traditional roles' that I was left with a smile on my face at the end just like the characters from South Korea's past reflecting back at my present. (Adam Hartzell)

The Salaryman ("Wolgeup-jaengi"). Directed by Lee Bong-rae. Screenplay by Yang Yun-shik. Starring Kim Seung-ho, Joo Jeung-nyeo, Eom Aeng-ran, Lee Su-ryeon, Bang Seong-ja, Ahn Sung-ki, Choi Nam-hyun, Park Am, Kim Hee-gap. Cinematography by Lee Byeong-sam. Produced by Yeona Film Company. 98 min, 35mm, b&w.

![]() The Marines Who Never Returned (1963)

The Marines Who Never Returned (1963)

As part of its ongoing mission to promote the cinematic treasures of South Korea's past, the 10th Pusan International Film Festival in 2005 held a retrospective on the work of Lee Man-hee. After the Korean War, Lee became actively involved in the film industry, debuting as a director with Panorama of Life (1961). Before passing away 30 years ago, Lee had produced a significant library of directorial works, some of which are considered classics of Korean cinema, such as the lost Late Autumn (1966) and the film I decided to revisit here as preparation for my attendance at Pusan, The Marines Who Never Returned.

This variation on an often trekked genre follows a platoon of South Korean marines who will eventually be commanded to hold back an advancing infantry of Chinese troops. The story begins, however, with a battle fought against North Korean soldiers in the ruins of a city street where both sides witness the orphaning of a young girl named Young-hui. The South Koreans quickly swoop in to save her from the crossfire. They will eventually become a collective of foster fathers for this young girl, or, as the subtitles refer to her, their "mascot." As they leave the battlefield victorious, Jeong-ik (Choi Mu-ryung - Red Muffler, North and South) discovers that lying amongst the dead masses of villagers killed by the North Koreans is his very own sister. The young girl informs Jeong-ik that it was Young-ja's brother who killed Jeong-ik's sister. Young-hui will later inform the platoon that Young-ja himself is not a North Korean communist, but a marine like them, explaining this just before Young-ja happens to join up with this very platoon. Young-ja's arrival underscores the divisions that existed within some Korean families concerning their loyalties during the war, an angle explored in future Korean films about the war, such as Kang Je-gyu's Taegukgi, and the resolution between Jeong-ik and Young-ja is a key element of the early part of the film.

Young-ja's arrival also underscores an argument by David Scott Diffrient, laid out in his contribution to the book South Korean Golden Age Melodrama: Gender, Genre, and National Cinema, that the South Korean war films of the Golden Age (1955-1972) were "Un-Gendering Genre" (162) by consciously adopting "...the emotional excess typically associated with melodrama and the woman's film" (151). Coincidences like Young-ja just so happening to be assigned to the same platoon as the man whose sister his brother killed are a staple of melodrama. Equally demonstrative of Diffrient's thesis, the platoon is commanded by a man fluid in his expression of gender, a man who shows a motherly concern when leading his men towards eminent death along with a requisite fatherly sternness when dispensing orders. Young-hui also underscores how the woman's film exists within the Korean Golden Age war film by being the platoon's mascot. For what is the intent of a mascot, from the Fighting Irish to the Red Devils, but to represent a mass mindset. In this case, the collective is just as much represented by this little girl as they are by associations with the military. Also, as Diffrient points out, Young-hui is afforded the task of naming these men. She even goes so far as to name one "Sissy" and instruct the men to step beyond their gendered assignments and be kind to "Sissy."

Young-ja's arrival also underscores an argument by David Scott Diffrient, laid out in his contribution to the book South Korean Golden Age Melodrama: Gender, Genre, and National Cinema, that the South Korean war films of the Golden Age (1955-1972) were "Un-Gendering Genre" (162) by consciously adopting "...the emotional excess typically associated with melodrama and the woman's film" (151). Coincidences like Young-ja just so happening to be assigned to the same platoon as the man whose sister his brother killed are a staple of melodrama. Equally demonstrative of Diffrient's thesis, the platoon is commanded by a man fluid in his expression of gender, a man who shows a motherly concern when leading his men towards eminent death along with a requisite fatherly sternness when dispensing orders. Young-hui also underscores how the woman's film exists within the Korean Golden Age war film by being the platoon's mascot. For what is the intent of a mascot, from the Fighting Irish to the Red Devils, but to represent a mass mindset. In this case, the collective is just as much represented by this little girl as they are by associations with the military. Also, as Diffrient points out, Young-hui is afforded the task of naming these men. She even goes so far as to name one "Sissy" and instruct the men to step beyond their gendered assignments and be kind to "Sissy."

Still, Diffrient's argument is that the South Korean war film is a mixture of genres, so the masculine prerogatives of war films remain. The marines take offense to a bar of Korean hostesses that is off-limits to Korean men, solely to be used by United Nations soldiers. After playfully, yet not so playfully, damaging the establishment with the pretext of paying for each item they damage, the prostitutes at the bar come around and allow these marines access to their commodified bodies. Although this scene can also be interpreted as a point of 'cultural resistance' since the marines are seeking access to bodies denied them by 'colonial' forces that they, as Korean men, feel "entitled" to, this is still a masculine and national conceit that requires women to subjugate their bodies for the men of the nation. In spite of all that, there is cultural resistance in this scene that does not rely on subjugating women, such as that exhibited by the marine played by the famous comic actor Ku Bong-seo (Obuja, School Excursion). This marine playfully uses the colonizer's language, and subversive descriptions of the colonizer's violence, to fool away the United Nations soldiers who arrive bearing gifts for the prostitutes, or, as they are called in English here, "The Sexy".

Underscoring the dialogue regarding the horrors of war, Lee also demonstrates this visually through slow panning of the rows of bodies of dead villagers in the beginning of the film rhymed with the many dead soldiers in the foxholes near the end. Such allows for interpretations of an anti-war sentiment. But as Jonathan Rosenbaum relayed in Movie Wars, Sam Fuller, a director who is similar to South Korean directors of the Golden Age in that he also experienced a war firsthand, felt even Full Metal Jacket was, as Rosenbaum paraphrased, "...another goddamn recruiting film" (70). Concerning The Marines Who Never Returned, the camaraderie and bonding amongst the uniformed men, such as the goofy dance scene in the tent or the king-of-the-mountain game, is just as compelling as the humanist sentiments within the dialogue. So, it might be more accurate to say that every war film is vulnerable to being a pro- AND anti-war film. (Consider the fact that The New Yorker called Saving Private Ryan the war film "to end all wars" yet the Bush II administration went on to prove such proclamations false.) Regardless of Lee's intent here, the shadow will accompany that which is focused on by the light. We are left with the simultaneous understanding of both the horrors of war and the attraction to war, which is why it is not ironic for such films to find appreciative fans on opposite sides of the political spectrum. (Adam Hartzell)

The Marines Who Never Returned ("Doraoji anneun haebyeong"). Directed by Lee Man-hee. Screenplay by Jang Guk-jin. Starring Jang Dong-hwi, Choi Mu-ryong, Koo Bong-seo, Lee Dae-yeop, Jeon Kye-hyun, Kang Mi-ae, Jeon Young-seon, Kim Woon-ha. Cinematography by Seo Jeong-min. Produced by Daewon Film Company. 110 min, 35mm, b&w. Rating received on April 11, 1963. Winner of Best Director, Best Sound, Best Cinematography at 3rd Grand Bell Awards.

As disappointing as it is that roughly 20 minutes of visuals are missing from the most complete extant print of Kim Ki-young's Goryeojang, the audio of those scenes is still with us. These partially missing pieces bring about an alternate horror in not being able to see what you hear. One of the scenes seen-less involves the rape of a character. And since what we have lost requires the audience to imagine what is taking place on screen, it is all the more terrifying because of it. This was an intentional tactic of a rape scene by Winnipeg indie director Sean Garrity in his recent film Zooey and Adam where the flashlights of a campsite are extinguished as the violence erupts. And Jafir Panahi presented a frightening moment of domestic abuse in The Circle hidden from view behind a closed door that kept opening slightly like the cover of a boiling pot. Yes, just like every cinephile, I would prefer we had a complete, pristine print of Goryeojang, but the unintentional result of scenes lost can bring a new horror to the modern day viewer.

Widower, now single mom, Keum (Joo Jeung-hyn) marries a man who already has ten sons . But when a shaman (Jeon Ok) prophesizes that Keum's son Guryong (Kim Jin-kyu) will kill these sons, the sons feel justified in using preemptive force to kill Guryong with a snake. This incident results in Guryong becoming disabled in his mobility and Keum and Guryong leaving the family Keum just married into. Several years after being ensconced away from the ten briefly brothers, Guryong marries a mute woman (Kim So-mi) whom the ten brothers kidnap in order to secure some of Guryong's land. Later, during an extreme famine the ten brothers exploit access to a well. This famine is what leads Gannon (Kim Bo-ae), a childhood love interest of Guryong's, to seek out Guryong later in order to beg food from Guryong. And, still, the ten brothers are not done with Guryong and everything he holds dear.

Widower, now single mom, Keum (Joo Jeung-hyn) marries a man who already has ten sons . But when a shaman (Jeon Ok) prophesizes that Keum's son Guryong (Kim Jin-kyu) will kill these sons, the sons feel justified in using preemptive force to kill Guryong with a snake. This incident results in Guryong becoming disabled in his mobility and Keum and Guryong leaving the family Keum just married into. Several years after being ensconced away from the ten briefly brothers, Guryong marries a mute woman (Kim So-mi) whom the ten brothers kidnap in order to secure some of Guryong's land. Later, during an extreme famine the ten brothers exploit access to a well. This famine is what leads Gannon (Kim Bo-ae), a childhood love interest of Guryong's, to seek out Guryong later in order to beg food from Guryong. And, still, the ten brothers are not done with Guryong and everything he holds dear.

Goryeojang is a film depicting a time of desperation for families, putting them in moral dilemmas that lead them to do things they perhaps wouldn't do if the lower needs on the Maslow hierarchy were met. Infanticide (the killing of children), invalidicide (the killing of the disabled), and senilicide (the killing of old people), are all sad realities in times of intense famine when resources are severely limited, but they likely happen much less than is often mythologized. As far as I know, there is no recorded instance of Inuit peoples putting elder family members on ice floats to die. According to The Straight Dope, it was likely a book (Top of the World by Hans Ruesch published in 1950) and movie (The Savage Innocents directed by Nicolas Ray and released in 1960) based on that book that put that myth firmly in Western minds. Likely equally a myth is the belief that elder Koreans were sent to the mountains to die during the Goryeo era. (The title of the film is actually the word for this folkloric practice.) This myth plays a part in propelling this film as does the stereotypes of the disabled and fears of the able-bodied imposed upon the disabled in the depictions of physically-disabled Guryong and his mute wife.

For those less familiar with Kim Ki-young, he was most known for being a horror film director working within an industry that liked to mash-up melodrama with all other genres. Goryeojang has a horror genre-required money shot near the end that can come across as campy today, but I imagine it was quite a shock for its time. (I myself couldn't help emitting the typical, horror-audience, sarcastic response, 'Oh, you did not go there!' while watching that scene on DVD.) It also features moments of shaman ritual that alternately act as partial documents of how these traditions were understood by the South Korean film industry at this time. An interesting bit of trivia regarding this film is that Kim accused Shin Sang-ok of stealing an image from a production still from Goryeojang of the mother being carried on an A-frame for his film Bound By Chastity Rule and a legal ruckus arose because of this. In this way, Goryeojang demonstrates yet again how Kim Ki-young could generate controversy inside and outside his films, becoming a cultural agent making a huge impact in his time and beyond considering the present day filmmakers who owe a debt to his bizarre, creative vision. (Adam Hartzell)

Goryeojang ("Goryeojang"). Directed by Kim Ki-young. Screenplay by Kim Ki-young. Starring Kim Jin-kyu, Joo Jeung-nyo, Kim Bo-ae, Kim Dong-won, Lee Ye-chun, Park Am, Jeon Ok. Cinematography by Kim Deok-jin. Produced by Korean Art Films Co./Kim Ki-young Production. 110min, 35mm, b&w. Screened at the 10th Asian Film Festival. Winner of Best Film, Best Director (Kim Ki-young), Best Art Director (Park Seok-in, Kim Hyeon-kyoon) at the 7th Buil Film Awards.

Last night I sat down and watched yet another Shin Sang-ok film. Unlike his other films that I have seen, this one has a strong element of comedy involved-mostly in the form of sight gags. I now know why Shin did not make many comedies. The movie itself is not bad but the comedic sequences are poorly timed and executed, although much of the fault may lie with the lead actor Shin Yeong-gyun who is also not known as a skilled comic actor. (The KMDB generously overlooks the fact that the film is at least in part a comedy and opts to list the movie as a historical melodrama).

It is the story of Byeong who, at the beginning of the film, we assume is a country bumpkin living in the mountains of Ganghwa Province, sometime in the Joseon Dynasty period. From the term doryeong others use to address him, we know that he is from nobility, but there is clearly nothing left of the fortune his ancestors might have had as Byeong lives in a clay and straw hovel with barely enough to eat. He gets by with his knowledge of what plants and roots are edible in the hillsides where he gathers straw and is assisted by a man he addresses as brother.

It is the story of Byeong who, at the beginning of the film, we assume is a country bumpkin living in the mountains of Ganghwa Province, sometime in the Joseon Dynasty period. From the term doryeong others use to address him, we know that he is from nobility, but there is clearly nothing left of the fortune his ancestors might have had as Byeong lives in a clay and straw hovel with barely enough to eat. He gets by with his knowledge of what plants and roots are edible in the hillsides where he gathers straw and is assisted by a man he addresses as brother.

After the king of the nation falls ill, Byeong's life goes through a dramatic change. It turns out that the young man is closely related to the ruling house and he is sought out by the Queen Mother to be groomed as the heir. For a man raised in the mountains where he could wander freely, living in the confines of the palace surrounded by servants and attendants is equal to living in prison. He is not used to the rich food, palace etiquette or sitting still. He longs for freedom to roam around as he pleases, as well as for his friend, Bok-nyeo, a girl that he grew up with and whom he had always treated as an equal.

He misses her so much that the Queen Mother agrees to fetch her and allow her to live at the palace as one of the attendants. Their happy reunion is short-lived, however, as, not long afterwards, Byeong is forced to marry a woman of royal blood. On his wedding night, the new prince escapes from his bride and joins Bok-nyeo on a secret visit into town where they meet with Bok-nyeo's mother who has opened a little tavern. Enjoying the country-style food, the prince has soon forgotten all protocol and is literally frolicking with people of all classes.

But princes do not frolic. The Queen Mother discovers what is going on and puts an immediate stop to it. And while Byeong is bemoaning his fate and the fact that he is not allowed to do anything fun, Bok-nyeo is taken before the Queen to face punishment for being a bad influence on the future monarch.

The plot synopsis above does sound like a weepy melodrama. It gets to be even more so from the point after the Queen finishes with Bok-nyeo, but it is the comedy that stands out most clearly in my mind. The first bit is handled very well such as when Byeong has fallen while in the mountains and his clothes are severely torn in the most unlikely way. He goes to Bok-nyeo who sneaks away to sew it for him. She manages to mend his shirt easily without him having to take it off but she faces a problem with the pants because the right leg has torn all the way up to the crotch. The pair comes up with a solution where Byeong can take off his pants behind a bush. Because Bok-nyeo is wearing pantaloons under her hanbok, she allows Byeong to wear her skirt so he will not be bare. Of course, the pair is discovered and a comic chase with the two looking like they are in drag occurs. What makes this scene work is not so much the situation, but how the characters relate to each other. It shows that they are very comfortable in their treatment of one another very much like equals or true friends.

Later in the film comedy does not work quite so well. Some parts of the prince's education, like how to walk without letting the tassels on the crown swing, are fine, but others like the diarrhea scene or the antics on the grass when first reunited with Bok-nyeo just go on forever. A liberal use of scissors in the editing room was required.

Had Shin decided to cut out the comedy in the film, I would have enjoyed Reluctant Prince a lot more. The story and acting are good. But the poor execution of the comedy makes me unable to fully appreciate the film. There are much better examples of Shin's work out there. (Tom Giammarco)

The Reluctant Prince ("Ganghwa doryung"). Directed by Shin Sang-ok. Screenplay by Lim Hee-jae. Starring Choi Eun-hee, Shin Young-kyun, Kim Seung-ho, Hwang Jung-seun, Kim Hee-kap, Han Eun-jin, Shin Seung-il. Cinematography by Kim Yeong-in. Produced by Shin Film. 126min, 35mm, b&w. Released on June 1, 1963. Total admissions: 100,000.

There was a moment while watching Kim Soo-yong's film Kinship where I was readying myself to cringe from intense political discomfort. It was when Won-chil was meeting a former sweetheart, Ok-hui, after returning to Seoul from studying in Japan. Ok-hui was preparing to tell Won-chil that she was now a 'Yankee Girl'. (Or, at least, this is what the English subtitles say. In the film the actual word used is "yanggongju", what is often translated in English as "Western Princess.") And just as she was revealing this secret, I was ready for her to be 'punished' by Won-chil because the patriarchy at that time required such warped justice in order to teach this Korean woman a lesson about 'tainting' herself with foreign men. I was preparing myself for the violence such distorted logic justifies. But all Won-chil did was somewhat forcefully push her back on to her bed and leave.

Was the patriarchal violence I was expecting going to be plot-related? Would she end up dying from an accident or by her own hand to teach the misguided lesson I assumed the film would lecture?

To my relief, Kim's answer to my questions over miles and years was no. What actually happens is she's allowed to change direction without any paternalistic teaching moments. She doesn't even have to 'redeem' herself really. She is simply allowed to walk away from the life of a sex worker for foreign military men to start a new life.

It was then that I recalled the scene at the bar where foreign military men go to chat up, dance, and sometimes later have sex with Korean hostesses. I recall the montage of the faces of the other women at the bar. Each one was permitted facial gestures of resistance. Some looked sad, some bored. But all provide a look that underscores the 'work' in 'sex work'. In their own way, they were showing a resistance through gesture similar to what Celine Parreñas Shimizu finds in some of the bar girls of the gonzo porn series 101 Asian Debutantes that she details in her close reading of Asian/Asian-American women in movie roles, ranging from pornography to mainstream to indie, in The Hypersexuality of Race: Performing Asian/American Women on Screen and Scene (Duke University Press, 2007). Rather than punish these women as patriarchy's slut-shaming demands, director Kim portrays a realm of Korean characters who have found kinship with sex workers, empathizing with the difficulty of their plight. Ok-hui's labor as a prostitute is presented as having parallels with Won-chil's day-laboring in construction, a job not available to Ok-hui due to the gender discrimination of this time. These women needed to make money for themselves and/or their family in one of the few means available to Korean women at this time before South Korea's later economic success. As a result, Kim's film refuses to judge these women negatively. Kim even includes another woman who resists, a war orphan whose adoptive mother is trying to instruct her daughter in the ways of a kisaeng in order to provide for the family later on. Her pansori-singing sounds even sadder given this reason behind the lessons. Eventually she runs away from her family, diverting from the trajectory her mother is trying to direct. Through this character, the film is noting that it isn't just Westerners who are sexually exploiting South Korean women. There's indigenous exploitation too.

It was then that I recalled the scene at the bar where foreign military men go to chat up, dance, and sometimes later have sex with Korean hostesses. I recall the montage of the faces of the other women at the bar. Each one was permitted facial gestures of resistance. Some looked sad, some bored. But all provide a look that underscores the 'work' in 'sex work'. In their own way, they were showing a resistance through gesture similar to what Celine Parreñas Shimizu finds in some of the bar girls of the gonzo porn series 101 Asian Debutantes that she details in her close reading of Asian/Asian-American women in movie roles, ranging from pornography to mainstream to indie, in The Hypersexuality of Race: Performing Asian/American Women on Screen and Scene (Duke University Press, 2007). Rather than punish these women as patriarchy's slut-shaming demands, director Kim portrays a realm of Korean characters who have found kinship with sex workers, empathizing with the difficulty of their plight. Ok-hui's labor as a prostitute is presented as having parallels with Won-chil's day-laboring in construction, a job not available to Ok-hui due to the gender discrimination of this time. These women needed to make money for themselves and/or their family in one of the few means available to Korean women at this time before South Korea's later economic success. As a result, Kim's film refuses to judge these women negatively. Kim even includes another woman who resists, a war orphan whose adoptive mother is trying to instruct her daughter in the ways of a kisaeng in order to provide for the family later on. Her pansori-singing sounds even sadder given this reason behind the lessons. Eventually she runs away from her family, diverting from the trajectory her mother is trying to direct. Through this character, the film is noting that it isn't just Westerners who are sexually exploiting South Korean women. There's indigenous exploitation too.

Kinship follows what seems like too many characters at times. Along with the family that adopts a war orphan, there is Won-chil's family. Although Won-chil's mother is still alive, his brother's wife is on her deathbed. His sister-in-law's ailment and his niece's physical disability were caused by his brother's initial scheme to make money by rummaging bombs for scrap, one salvage mission going terribly array. There is also their neighbor who has more money than everyone else and uses that money to buy a younger wife. (Like the sex workers, this younger woman also finds a means to rebel against her economic situation.) This man has an antagonistic relationship with his son, while his son has feelings for the war orphan adopted next door. Tensions arise between these various parties, such as Won-chil's older brother's resentment for the opportunities afforded Won-chil. In the middle of the film, it seems like everyone is fighting in that overly emotive way that can cause the modern viewer to feel disconnected from the action and dialogue on screen.

In spite of all this fighting, that subplot I mentioned at the beginning lets you know that fates are going to shift among these families. In this South Korean film, the nation isn't saved on just the backs of women. This is a family effort, a neighborhood watch.

This is not the first film by Kim to surprise me with where he takes the narrative. Read my piece below on Kim's A Seaside Village (1965) and you'll see how unexpected it was to find such a portrayal of female sexual agency in a film of such a conservative time as 1960's South Korea.